By Rita Faraj

Today, France has the largest Muslim community in Europe. Successive French governments sought to integrate Muslims into their broader social environment, but many attempts have failed for interrelated reasons, most notably the absence of a serious strategy to resolve the crisis of suburbs (2005-2017).

Following the Paris terrorist attacks of 2015 carried out by radical Islamists, the French government dealt with the situation with great care to absorb the trauma, seeking to distinguish between Islam and terrorism. While the majority of the French intelligentsia did not grasp what happened based on dual cultural confrontation: ‘either us or them.’ After this seismic event, the French authorities began working on establishing the ‘Foundation for the Islam in France’ in order to make Islam compatible with the values of the French Republic, especially secularism. This step was a continuation of previous steps initiated in the 1980s.

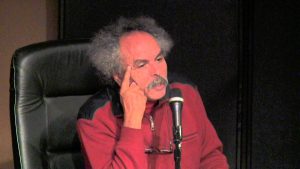

The topic of Islam in France raises today old and new issues related to important challenges, namely: problems of integration, conflict between religious and civil realms, deterrent secularism, retraining of imams and fear of the growth of extreme right. This is accompanied by the growth of populist anti-immigrant rhetoric amidst the greatest illegal immigration movement witnessed this century from southern Mediterranean shores towards the Old Continent. In order to better understand these and other issues, Al Mesbar Studies and Research Centre in Dubai conducted an interview with Professor Mohamed Al-Cherif Ferjani.

Ferjani, professor of political science at the University of Lyon II (France), is interested in research areas related to political science, comparative study of religions and history of political and religious ideas in the Arab world. He is one of the most prominent experts in the relationship between religion and politics in Islam. He received a PhD in political science from the University of Lyon II in 1989. The title of his dissertation was Secularism and Human Rights in Contemporary Arab Political Thought (in French). He also published in French: Le politique et le religieux dans le champ islamique’ and ‘Islamisme, laïcité, et droits de l’homme.

Here follows our interview:

Q: The 2015 bloody attacks of Paris left a deep wound in the collective memory in France, and the French State dealt with in utmost care about which much was written. On the other hand, some voices called for the French authorities to deal firmly with immigrants, accompanied by high levels of fear of Islam. Less than three years after these terrorist attacks, did France succeed in overcoming its fear of Islam?

Fear of Islam precedes 2015 Paris attacks. This fear is linked to several factors; most notably the disintegration of the Soviet Union, which as an actual or delusional enemy represented for decades the enemy upon which the Western camp identity was built. After the collapse of the socialist system, Vladimir Federovski, a Russian specialist in Western affairs, said: ‘We are going to deal a fatal blow to one of the foundations of your existence, and deprive you of the enemy on which your entity was founded.’

Once the socialist system collapsed, search for a new enemy began. The character of this enemy started to take shape since the end of the seventies, with the Iranian revolution and the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran in 1979. Little by little, the ‘green enemy’ began to replace the ‘Red Enemy’, and the fear of Islam in Europe began since then. In the early 1990s, Jean-François Poncet, the French foreign minister at the time, wrote in Le Monde: ‘There are three challenges facing the establishment of Europe: an ecological challenge, an economic challenge represented by the economies of Southeast Asia and an ideological challenge represented by Islam.’ He did not say Islamist movements, but Islam. In response to him, I have been writing since the beginning of 1990s about the danger of Islamophobia or fear of Islam.

The French authorities spoke about fear of Islam only after the danger of this phenomenon, grew almost twenty-five years after the fall of Berlin Wall. The factors behind the emergence of Islamophobia at the end of the twentieth century will continue to exist unless political, economic and cultural model, not only in Europe but throughout the world, succeed in creating new social, economic and political integration patterns. The reason for this is that the models built in the 19th and early 20th centuries are no longer able to respond to the needs of man in order to give meaning to his existence, and to find synergies that allow him to accept life and have confidence in himself and in the future. Here lies the ailment. Unless these dilemmas are addressed and solutions are found to the problems facing the human community, we will always move from fear to fear and from ideologies calling for to ideologies that indicate the danger of “war of cultures” and “clash of civilizations” to draw attention to the real causes of the human tragedies.

Q: Former Minister of the Interior Bernard Cazeneuve launched the ‘Foundation for the Islam in France’ in order to make Islam compatible with the values of the French Republic, especially secularism. What are the steps taken by this institution so far?

In fact, Foundation for the Islam in France’, launched by Bernard Cazeneuve, is no more than a new attempt in a series of efforts by the French authorities since the late 1980s, which began with Pierre Guécs when he was minister of interior, followed by Jean-Pierre Chevènement, Sarkozy and several other French ministers. Cazeneuve act was part of the reaction to the Paris attacks. These efforts seek – as I mentioned – to integrate Muslims into the Republic, knowing that France gave up since 1980s the illusion of the temporary presence of Islam in France and the illusion of the return of Muslim immigrants to their countries. In this period, a new established awareness sought to develop mechanisms for the integration of the Muslim communities. There were previous attempts such as teaching immigrants their original languages and cultures to enable them to return to their countries. Later, mosques were permitted to be built, and then attempts were made to include Muslims in electoral lists.

Islamic institutions in France face a problem in training imams, especially as they present sermons in mosques that have nothing to do with concepts of integration, sermons that distance Muslims from their milieu and increase their isolation and alienation in European societies. The institutions I referred to are founded on an exclusionary vision that places Muslims in conflict with other religious groups and other cultures. The French authorities realized the seriousness of this, and sought to mitigate its intensity by inviting supervisors of mosques and fatwa institutions to adopt a discourse that makes Islamic beliefs compatible with the civil life of a secular multi-religious society with multiple intellectual and spiritual orientations. In this context, the ‘Foundation for the Islam in France’ tried to assist in the training of imams in private university institutions, as it is difficult to do so in public universities due to inherited suspicious, if not hostile, relations toward religions. Thus the authorities resorted to private Catholic universities to develop courses for the training of imams. Most of the members of this institution, headed by Jean-Pierre Chevènement, are secular Muslims, such as Ghaleb bin Sheikh, who demanded the recognition of Muslims like other religious groups such as Christianity and Judaism, and treating them on equal footing with others to apply true secularism that does not distinguish between citizens on the basis of their religious affiliations. This institution helps in developing educational and informational programs that deal with human rights organizations and associations. The aim of these programs is to reduce tension in the relationship between Muslims and the communities in which they live in France and reduce tension in the relationship of the French society with Muslims, in order to convince Muslims that they are French, their place is alongside the rest of the French and Islam cannot and should not be reduced into Salafist and radical tendencies that refuse the integration of Muslims into their societies. This is what the institution seeks, but this process should be supported by Islamic institutions to overcome the isolation discourse that considers integration of Muslims as a threat to their faith.

Q: The French historian Jean Baubérot considered in his book Les laïcités dans le monde (Secularisms of the World) that the French secularism is a “deterrent secularism” because it deals harshly with public religious symbols. This contradicts the freedom of religious expression provided for by the 1905 law, which gave special status to religions even though it did not recognize any official religion, i.e. the French Republic guarantees freedom of belief for all. What is your opinion regarding Jean Baubérot’s depiction of deterrent secularism and its conflict with the 1905 law?

Jean Baubérot is a friend, and we work together, he is a historian and sociologist specializing in the processes of secularization and secularism. Since there are in France – as in the Arab world – doctrinal approaches to secularism, he tries to oppose this doctrinal treatment, which considers secularism an anti-religious ideology in general. His depiction of the French secularism as a deterrent secularism is somewhat unfair, since secularism in Europe and France has streams. Even the 1905 Law is in itself inconsistent with the writings of Ernest Renan, Emile Combes, and others who considered secularism to be at war with religion. At the forefront of the religions they wanted to resist at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, we find Christianity itself. The 1905 Law came to put an end to the war between Catholic France and secular France. It guaranteed freedom of belief and religious observance without discrimination, and allowed the Republic to deal impartially with all religious communities.

Under the pressure of globalization and international changes, the Fifth Republic gradually abandoned the social role of the State, which led to the phenomena of impoverishment and marginalization that have been exacerbated by the abandonment of economic and social rights and the secure interests of those rights, and the consequent exclusion of marginalized groups, including migrants. This led to some confusion in the trends of all the patterns of integration prevailing for decades, which produced reactions including deterrent secularism. Dar Al-Tanweer issued my book entitled “Secularization and Secularism in the Islamic World” in which I refer to this discussion, and point out that secularism cannot exist in the absence of its social, political, economic and cultural conditions. The existence of a perfect ground on which secularism is based is inevitable. In case such ground is reduced, it is inevitable for secularism to fall back under the pressure of counter-forces. People will resort to old solidarities that are incompatible with secularism, clannism, tribalism and sectarianism, since man by nature cannot live alone as a human being, and needs social connections; he is “civil bu nature” – as Ibn Khaldun and Aristotle say.

In the last decades, France witnessed the so-called phenomenon of ‘new philosophers’ such as André Glucksmann, Bernard-Henri Lévy and others, who adopt a sharp political discourse, unlike previous philosophers such as Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida and Pierre Bourdieu, who were more closely related to the creation of ideas and formation of awareness. How do you explain this phenomenon?

The so called ‘new philosophers’ are not philosophers but clergy of the established system, as the American thinker Noam Chomsky calls them. They are the counterparts of what we call the jurists of the sultan, and whom Jean-Paul Sartre and Paul Nizan call the watchdogs of the regime. Perhaps the crisis of philosophical thought is a phenomenon of what I have mentioned about the crises of models that emerged in Europe in the 18th, 19th and 20th century. When philosophical thought declines, a ground for the emergence of ideology is created, since ideology flourishes when philosophy declines. Ideology is the function of the clergy of authority and not that of philosophers who help man to develop the ability of critical thinking and self-reflection, instead of adopting ready-made solutions. What we call new philosophers are the group of clerics who want to guide human thought instead of providing the tools for people to think for themselves. Philosophy should return to resume its role in the formation of intellect and development of its abilities to think for itself; this requires granting philosophy an important position in our educational programs. Unfortunately, this is not taking place in all countries. Even in France, the status of teaching philosophy has declined. No need to mention the Arab countries where philosophy is almost non-existent in educational programs, and is surrounded, where it exists, by other programs whose aim is to limit their influence. The reason being that Arab countries do not want to create a young generation capable of self-reflection and critical thinking.

Q: Observers notice the growing voices and presence of the extreme right in Europe in the past two years, and France has not been spared. The right has risen with confusion of the international leadership of the world, the collapse of world political values and the emergence of heads of states without a previous political history, such as US President Donald Trump. How do you explain the rise of the extreme right and populist rhetoric in Europe? And to what extent does this right reflect the conflict of identities?

Indeed, the extreme right is part of the conflict of ‘fatal identities’- as described by Amin Maalouf – which are the identities that advocates the ‘clash of civilizations’ resort to. Islamic movements, being one of the most important representatives of which in the Islamic world, like the extreme right, adopt an identity discourse based on exclusion and religious, ethnic, cultural and intellectual hatred of others. These identities have grown and become the refuge of the victims of savage capitalism, which controls the globalization system today with the help of those benefiting from it to push victims of globalization to fight among each other instead of solidarity and unity to resist the cause of their tragedy.

France is not isolated from the processes of liberal globalization, which deprive man of the elements that help him to make sense of his existence. Today, all marginalized people in the world, including migrants and other broad social groups who were allowed to have a place in society, are suffering from various kinds of deprivation as a result of the new economic policies imposed by savage capitalism. This leads to rival fanaticisms and ideologies in light of the noticeable decline of the social role of the state. Conflicting identities among individuals and groups seek refuges that help them cope with the difficulties of life. Thus, the ground that nurtured ethnic, tribal and religious affiliations became available, due to loss of old solidarities, under declining job opportunities, exacerbation of failure in school and the low living conditions.

The extreme right phenomenon is what produced heads of state like Donald Trump. We have no differentiate between him; Marine Le Pen, the leader of France’s National Front Party; the leaders of the far-right parties in Austria and other populists from across the spectrum. Fatal identities among Muslims must not make us forget fatal identities in Israel, America and Europe. These identities feed each other, and the right in Europe draws its strength from Islamist movements. We know that these movements allied themselves with the United States and former British colonialism, and communicated in various forms with the colonial powers, including Israel.

We are faced with conflicting identities phenomenon – as you mentioned in the question – but closed and distorted identities, a conflict based on an ideology that serves only extremists and those benefiting from the marginalization of social groups throughout the world. A conflict that falls within the framework of the savage capitalist mechanisms. In his book Jihad vs. McWorld, political scientist Benjamin Barbar explained how globalization, which is essentially a globalization of economic, consumption and living patterns in America – denoted by ‘McWorld’ – helps developing types of resistance – indicated by the term ‘Jihad’ – because they are based on the desire to return to new religious and tribal affiliations that refuse democracy, freedom and human right values. These fatal identities fall within a strategic context aimed at preventing the rapprochement among peoples and all forces that have interest in rapprochement and solidarity to break the shackles of this savage globalization.