By Dr. Haytham Mouzahem

Last week, on Valentine’s Day in Saudi Arabia, prominent cleric Ahmed Qasim al-Ghamdi — a former director-general of the “Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice, the kingdom’s “religious police” — made a remarkable statement. He opined that Valentine’s Day is a positive social event, not a religious one. He advised that, like Mother’s Day, Teacher’s Day, National Day, birthdays, and wedding anniversaries, it serves purely to enhance the human bond — and Islamic law poses no objection to it.

In the past, Salafi clerics had forbidden the celebration of Valentine’s Day and, for that matter, any commemoration of any annual event other than the Islamic religious festivals of Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha.

Al-Ghamdi’s new fatwa reflects the ongoing, gradual opening up of Saudi Arabia. His acceptance of Valentine’s Day was a welcome response to a pent-up demand: After nearly two decades of extremism, terrorism, and destructive conflict in Saudi Arabia, millions of Saudis want to celebrate love and joy in a secure, peaceful environment. The former tragedies had been ideologically grounded in a seemingly endless procession of fatwas by radical clerics and Salafi jihadists whose superficial understanding of Islam called for a rejection of love, tolerance, and acceptance of the other. The following verse from the Qur’an apparently meant little to them: “And from His Signs is that He created for you mates from among your own kind, that you may find comfort with them, and He planted love and kindness in your hearts; surely there are signs in this for those who reflect.” (Surat Al-Rum, verse 21) It means that God created to live together in love, affection, and empathy.

The spirit of the Qur’anic verse also finds expression in a tradition of the Prophet Muhammad in which he said, “No one believes (in Allah) among you until he loves for his brother what he loves for himself.” Another memorable saying, from the prophet’s great-great-grandson Imam Muhammad al-Baqir (677-733 CE) asks, “[What] is religion but love?” Indeed, dozens of Qur’anic verses and prophetic sayings call for love, tolerance, warm relations with parents and relatives, and amity with neighbors.

Yet the corpus of Islamic tradition has seen many distortions and misinterpretation which fed into an extremist mindset, justified violence and terrorism, and stigmatized tolerance, love, and joy. Clerics have complicated Muslims’ lives by banning practices which both the letter and the spirit of tradition do not oppose. Their worldview was anathema to the Qur’anic verse, “God intends for you ease and does not want things hard for you” (Al-Baqarah, verse 185). The statement is a signal that what the tradition does not forbid is implicitly permitted.

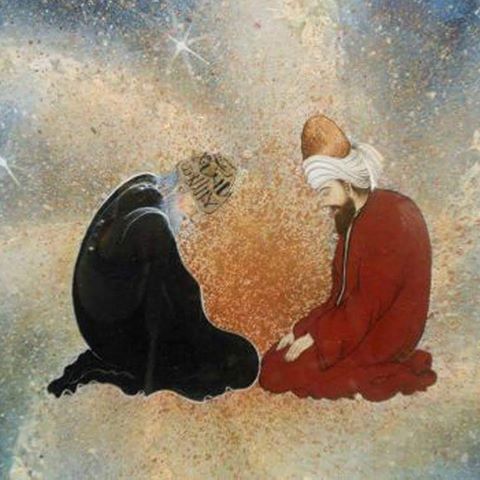

In light of the legacy of Islamist legalist extremism and the jihadist carnage it has inspired regionwide, it is not surprising that many Muslims today — not to mention non-Muslims — have turned to Sufi Islam to satisfy their spiritual needs. The past decade has seen a resurgence in interest in Sufi literature — in particular the works of Jalaluddin Rumi, which have seen new translations from Persian into Arabic, Turkish and other languages.

The novel The Forty Rules of Love by Turkish writer Elif Shafak, translated into more than 30 languages, has also attracted attention among Western, Turkish and Arab readers, and become a best-seller in Turkey. Highlighting Islam’s mystical tradition, it has become a kind of “gateway reading,” drawing in a new generation to the works of Rumi, Tabrizi, and other mystics. Shafak’s novel speaks to the universal yearning for spiritual fulfillment and liberation from the exhausting pursuit of material gain.

While some have sought to weave a range of unsound practices into Islam’s mystical strand, authentic Sufism can provide balance and a salubrious emotional experience of Islam — an especially vital corrective for those who have been burdened by extremist impositions.