Abstract

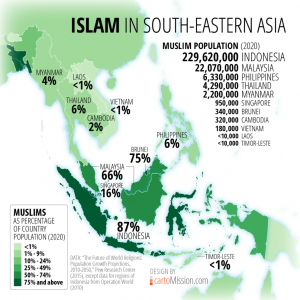

At the time when Southeast Asian Nations are aspiring to become, according to the Vision 2020, more outward-looking region, living in peace, stability, and prosperity, with a regional partnership in development, the region is facing a serious threat emanating from terrorism, both homegrown as well as international terrorism. The region has witnessed a series of terrorist attacks carried out by groups closely linked with Al-Qaida or Daesh. Their use of Islamic terminologies, in order to get their acts legitimized, they often propagate to aiming at the re-establishment of Caliphate or a similar Islamic rule controlled by them. The region, however, unlike many other Islamic regions, have not witnessed Islamic invasions in the middle centuries. Islam in South-East Asian states has spread mostly with peaceful messages of Sufis and traditional scholars, without having involved in militaristic competitions against the local rulers. As a result, most of the local rulers and their subjects chose Islam as their religion without becoming involved in a military confrontation. Most of the Muslims in the region are Sunni Muslims and followers of Shafii School of jurisprudence.

As of now, there are nineteen terrorist groups active in Indonesia, five in Malaysia and three groups in the Philippines who have either ideological or logistical relations with Al Qaeda and its affiliated terrorist groups. Many of these groups have their origins in the anti-Soviet Jihad back in the 1980s and their fighters returned with militant training and hardened ideological mindset in order to overthrow their states. Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), for example, emerged as one of the most radical groups in the region that spread its network and terrorist activities all over the region. The war against terrorism in Afghanistan and Iraq had weakened the organizational and logistical infrastructure of Al-Qaida which also affected the local groups in South East Asia. But the rise of Islamic State in Iraq and Syria provided these groups with a fresh opportunity realign themselves with ISIS or renew the Al Qaeda network with the help of local Islamic groups. This rise of another wave of radicalism in the region alarmed the regional governments and they started working on a regional strategy that would include both security and intellectual measures to prevent their youth from radicalization and joining the Al Qaeda or the ISIS.

This paper aims at documenting the origin and the rise of terrorist groups in Southeast Asia and the measures being taken by the states and the regional groups in coordination with the international community. The report will also look into the intellectual sources of radicalization in the region and how different Islamic groups have employed Islamic texts to use them for radicalization.

Key words: South-East Asia, Terrorism, Al-Qaida, ISIS, Islam

Introduction

The Southeast Asian Nations’ Vision 2020 aimed at an outward, peaceful, stable, and prosperous future. With this vision, Singapore, Malaysia, and the Philippines soon became the most visited place in the world, attracting investment, tourism and students from all over the world. Indonesia is leading the region with its stable growth since a decade maintaining an average of 5.3% for the last many years.[1] According to OECD report 2019, the labour market, private consumption should expand robustly, consistent with the trend since 2007. Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines and other countries have demonstrated significant economic stability over the last decade. This has brought the change in global power shift from Middle East to South Asia, dubbed as “Pivot to the Asia Pacific” within American policy debate. The region has also one of the steadiest demographic growths leading the region to remain as the attraction of global investment to tap into the healthy, trained and young labour market with 608 million populations.

The last few decades have also observed the rise of extremism and terrorism in the region emanating from different sources, mainly from the Islamic reactionary groups. The rise of such extremist and reactionary groups in the region poses a serious threat not only to the growth of the region but also the security environment for the global political and economic order. Terrorist attacks and terror groups’ cells have been reported from almost all countries of the region, from Thailand to Indonesia. Many of the groups operating in the region claim to champion a Salafi version of Islam which according to their ideology is more puritan than other versions of Islam. Islam as the biggest religious belief practiced by approximately 300 million population of the region, majority of them in Indonesia and Malaysia, has been misused and misinterpreted by several politically motivated religious groups in the region. Most of the Muslims of the region are Sunni Muslims following the Shafi’i School of jurisprudence; they are not a homogenous religious community, however.

Most of the religious groups in the region have developed their own local interpretations of Islamic practices; some of them are inspired by overseas interpretations originating from Egypt, Qatar, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iraq in recent years. The region has evolved its own brand of Islamic education traditions, known as pondok or pesantren, somehow different from that of South Asia’s Madrasas. According to many reports, these education centres failed to integrate with modern nation-states’ educational initiatives and developed a degree of alienation or mistrust towards modern education establishment. There are nearly 14000 such Islamic schools in Indonesia. The gruesome bombing of Bali was the first time when the links of terror incidents were traced to some of these schools, influenced by the Jemaah- Islamiyah (JI) and the Majlis Mujahidin Indonesia (MMI).

Like many other terrorist groups in the Middle East, the South East Asian terror outfits have also close links with the Afghan war of the 1980s, which has brought thousands of militants from all over the Islamic world to fight against the Soviet invasion. Abu Bakar Bashir and Sungkar along with Abu Jibril had all participated in the Afghan war and had returned with a hardened ideological outlook to change the Indonesian system, which in their views no longer left enough Islamic ideas. They established a series of Islamic institutions across Indonesia and inspired thousands of students to come and learn Islamic education. Other than traditional Islamic learning centers, the governments of the region as well as private foundations tried to establish modern universities with Islamic outlook. Among them are Malaysia’s International Islamic University (officially established in 1983), the Syarif Hidayatullah Islamic University, (renamed in 2002 from its earlier name State Institute for Islamic Studies). Analysts believe that these Islamic centers have been used by extremist groups to recruit Jihadists.

As stated, the rise of radical groups in the region started mainly from the Afghan war when the returnees of the Afghan Jihad refused to lay down their arms and integrate with the mainstream society; instead, they mobilized public opinion to overthrow their regimes. Inspired from the Afghan Jihad, the returnees established several groups, at least 19 groups in Indonesia, five groups in Malaysia and three groups in the Philippines that have their background with an international terrorist network of Al Qaeda or ISIS.

The spread of social media provided an opportunity to these groups to use the platform to disseminate their ideas as well as influence and recruit the young minds.[2] Several researchers have shown that these groups have effectively used YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and other social networking sites to spread their messages and their goals. Because of its accessibility, affordability attracts a lot of people at one point.[3] In acceleration of their growth, Al Qaeda and ISIS are persistent supporter of social media.In 2015, Singapore-based International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR) listed at least 300 extremist websites, forums and social media accounts in Southeast Asia, a majority of them containing materials published in Bahasa Indonesia or Malay language.[4] Radicalization could lead to recruitment. In most cases, there are primary nodes offering assistance to those who have intentions to be a fighter.

|

Name of the groups |

Country |

Founder |

Founding Year |

Key figures (wanted by Interpol or countries) |

Estimated members |

Banned or listed as a terror group by (UN, or Countries like USA) |

Any UN/UNSC Resolution against it. |

|

Jemaah Islamiyah(JI) |

Indonesia |

Abu Bakar Bashir and Abdullah Sungkar |

1993 |

Abu Bakar Bashir, Zulkarnaen, Umar Patek, |

5,000 approx |

In 2002 under the list of FTO. In 2010 banned. |

Resolution 1267 |

|

JamaahAnsharutTauhid |

Indonesia |

Abu Bakar Bashir |

2008 |

Muhammad Akhvan |

3000 and 5000 |

2012 |

Foreign Terrorist Organization list by US |

|

Abu Sayyaf |

Philippines |

1991 |

RadullanSahiron |

150 approx |

In 1997 under the list of FTO. |

paragraph 8(c) of resolution 1333 |

|

|

Patani United Liberation Organisation (PULO) |

Thailand |

Kabir Abdul Rahman |

1968 |

20,000 claimed by PULO |

– |

– |

|

|

BarisanRevolusiNasional (BRN) |

Thailand |

Haji Abdul Karim Hassan |

1963 |

Abdullah is wanted for treason under a Department of Special Investigation arrest warrant. Mr Tuanpeng most wanted according to the police. |

– |

– |

|

|

Kumpulan Mujahidin Malaysia (KMM) |

Malaysia |

Zainon Ismail |

1995 |

70-80 Members |

|||

|

Jemaah Islamiyah(JI) |

Malaysia |

Abu Bakar Bashir |

1993 |

Mohamad Rafi Bin Udin |

5,000 approx |

paragraphs 2 and 4 of resolution 2368 |

|

|

ArakanRohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) |

Myanmar |

Ataullahabu Ammar Jununi, |

2013 |

500-600 |

Myanmar’s Anti-Terrorism Central Committee declared ARSA a terrorist group on 25 August 2017 |

– |

Country Profile: Indonesia

A country of 260 million populations, Indonesia’s 87% population adheres to Islam and a majority of Muslims practice Sunni and Shafi’i School. Christianity, Buddhism and Hinduism are other prominent religious groups. Islam is known to have come to Indonesia only in early twentieth century when Arab travellers and Sufis were exploring the world. As there were no direct military operations ever launched by any Arab, Iranian or Central Asian Muslim ruler in South East Asia, the spread of Islam has observed a prolonged social dialogue between the travellers, traders, Sufis and the local populations. Most of the local Buddhist or Hindu Kings accepted Islam along with their families and subject and then they continued and expanded their Kingdoms across the Pacific. The culture of dialogue brought a new tradition of Islam, different from state power and war politics.[5]This made Indonesia a unique model of Islamic society where a blend of Islam and previous religions continued in their daily lives and cultures. Several Buddhist or Hindu festivals and their cultural traditions remain widely practiced by the local Muslim population, despite their becoming Muslims.[6]

The terrorist attack on the World Trade Centre on September 11, 2001, brought Indonesian extremist groups on global radar. Some of the groups with old linkages with Al Qaeda or Afghan Mujahideen were found to have their extremist indoctrination continued. The most extremist group among them, Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) carried out a terrorist attack on foreigner tourists in Bali, exposing the vulnerability of South East Asia to these terror groups. The JI had already spread its networks beyond Indonesia, mainly in Malaysia, Philippines and Singapore. JI is an active terrorist group with historical links to Al Qaeda.

The JI was founded by Abu Bakar Bashir and Abdullah Sungkar with an aim to the establishing an Islamic caliphate by overthrowing the Indonesian government. It has been considered an extremist organization that refuses to accept the democratic state system. The JI has its roots in Dar ul Islam a radical Islamist movement that sprang up in Indonesia in the 1940s during the national liberation struggle against Holland.[7] The outbreak of sectarian violence in Ambon (in the Malukus) and Poso (on Sulawesi) provided JI with opportunities to recruit, train and fund local mujahidin fighters to participate in the sectarian conflict in which hundreds died[8].

Abu Bakar Bashir

In 1972, Bashir founded Al-Mukmin boarding school with friend’s Abdullah Sungkar and others. Intelligence agencies and the United Nations claim Abu Bakar Bashir is the spiritual head of Jemaah Islamiyah(JI) and has links with Al-Qaeda.In August 2014, he publicly pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), the self-proclaimed Caliph of his new and short-lived Caliphate. Bashir has expressed his sympathy for Osama Bin Laden, but he didn’t “agree with all of his actions.[9]“I support Osama Bin Laden’s struggle because his struggle is the true struggle to uphold Islam” Bashir had expressed his views soon after he was accused of the Bali bombing in 2002.[10]On September 3, 2003, an Indonesian court convicted him of plotting to overthrow the Indonesian government. Bashir was sentenced to four years jail term. As he was to be released on May 2004, after his jail term was reduced, his hands were found in another terrorist attack. He remained in the jail to be tried for the charge. Indonesian authorities have to act swiftly as pressure from the United States and Australia was mounting.[11]JI developed close links with international terrorist organizations, mainly Al-Qaeda and its different affiliates. Beside JI other terrorist groups in Indonesia are Mujahidin Indonesia Timur (MIT) and Jamaah Ansharuut Tauhid (JAT). Since 2002, JI had carried out several terrorist attacks that have killed dozens of civilians and officials. Some of the most damaging attacks that he either took responsibility or were attributed to him are:

- August 17, 2015: Attack on Erawan shrine in the Thai capital, Bangkok.At least 22 people died and more than a hundred injured.

- July 17, 2009: Bomb blast at Ritz Carlton and JW Marriott hotels in Jakarta, Indonesia. 11 killed.

- October 1, 2005: Suicide bombings in Bali. 20 killed.

- September 9, 2004:Suicide car bombing outside the Australian Embassy in Jakarta. 10 killed, hundreds injured.

- August 5, 2003: Car bombing at the JW Marriott Hotel in Jakarta. 10 killed.

- October 12, 2002: Major bombings in a nightclub of Bali. 202 killed, most of them were foreign tourists.

Following the Asian financial crisis and the 2008 economic crisis, Indonesia undertook several reform initiatives that led to an intense social and political debate, then exploited by these extremist groups for their anti-government and anti-minorities rhetoric.[12]To counter the increasing influence of radicalization, the government revised the 2003 Anti-terrorism law (ATL), which allows police to pre-emptively detain terrorist suspects for 14 to 21 days before deciding to release or prosecute them.[13] The Indonesian government has recently formed the National Anti-Terrorism Agency (BNPT), an independent body to address the threats emanating from terrorism and extremism.[14]In 2018 alone, 376 terror suspects were arrested and 24 suspects were neutralized in counterterrorism operations.

The rise of ISIS in 2015 and its appeal to global Muslim communities to support their so called Islamic Caliphate saw significant interest among radical groups such as the JI and other South East Asian groups to support the ISIS. Many radicalized youth traveled from Indonesia to Iraq and Syria to join the ISIS and or other terrorist groups.[15] According to the UNODC Report, at least 671 Indonesians, 95 Malaysians, 4 Filipinos had travelled to Iraq and Syria to join ISIS. According to Indonesia’s National Counter-terrorism Agency (Badan Nasional Penanggulangan Terorisme, or BNPT), around 514 Indonesians had left the country to join various militant groups in Syria by December 2014.[16]

The Philippines

Like Indonesia, the Philippines too came in contact with Islam in the thirteen century when the Arab traders started arriving in the Sulu Archipelago and Jolo. And soon the local rulers started accepting Islam, mostly in the Southern region. By the end of the fifteenth century, European fleets, mainly from Spain started arriving and with them were Christian Missionary preachers who successfully promoted Christianity in the region. This led both Muslim and Christian population to live in a relative competitive environment, sowing the seeds of rivalry between Mindanao, Sulu, Cebu, and Luzon based Muslim centers and the newly converted Christian urban centers.[17] With Colonial rule continued for three centuries, the Muslim population decreased from being a dominant population to merely 5.6% of the Philippines’s total population. Bangsamoro, a southern Muslim dominant province has remained a battleground against the Spanish and American colonial rule and then claimed by Malaysia, for having been historically and culturally very close to Malaysia. The repression of Muslim minorities, after the American forces left the Philippines in 1946, led the region in direct confrontation against the centre, a struggle that turned violent and remained inactive militancy until a few years ago. The Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) and Raja Suleiman Movement (RSM) are the three major militant groups that have successfully exploited the conflict in order to radicalize the local Muslim population.[18]Abu Sayyaf had declared its support to the Islamic State in 2015. Founded in 1991, the Abu Sayyaf group and its leader Abdurajik Abubakar Janjalani were deeply inspired by Iran’s Islamic revolution in 1979 and had fought in Afghanistan before returning the Philippines in 1990. They started their radical narrative by discrediting the Moro Liberation National Front, which after a prolonged armed struggle, had entered an agreement of power sharing with the government in 1989. The creation of Abu Sayyaf by the two Afghan war returnees came with strong support from several International Islamist groups based in the Gulf. Since 1991, the Abu Sayyaf inflicted a massive terror campaign from bombing to kidnapping.

- On July 31, 2018, a suicide bombing was carried out in Lamitan immediately owned by the ISIS news agency Amaq as the handiwork of ISIS Philippines’ chapter.

- On June 13, 2016, a Canadian hostage, Robert Hall was executed. The next week on 21 June, seven Indonesian sailors were also taken into hostage.

- On July 28, 2014, Abu Sayyaf members carried out a deadly attack on civilians travelling for Eid, killing at least 21 civilians in Sulu.[19]

Abu Sayyaf’s primary sponsors were Osama bin Laden, his son-in-law Mohammed Jamal Khalifa, who helped Abdurajik Abubakar Janjalani establish Abu Sayyaf. Its relations with ISIS remained murkier as the group once declared its allegiance to the self-declared Caliph Baghdadi but later on, Abu Sayyaf maintained a strategic silence on supporting the ISIS.

Since the start of the global war on terrorism, the terrorist groups around the world have faced immense pressure in channelizing their financial and human resources. The counter insurgency plan introduced by the former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo had received International support, including from the Bush administration. At the same time, development projects were initiated in Muslim majority Southern districts, Jolo and Tawi Island. The Bush administration contributed some $260 million as development aid.[20] At the same time, negotiations with militant groups such as MILF were initiated to encourage these groups to de-link themselves from the Indonesia based Jemaah Islamiya, Abu Sayyaf or Al-Qaida.

Thailand

In Thailand too, Islam arrived with traders and travellers in the thirteenth century to the Malay Peninsula. A majority of Muslims in South Thailand are from Malay ethnicity, while the mainland’s Muslims are Thais. The relations between Muslims and non-Muslims remained very cordial for a long time, except when the nation-state boundaries were re-carved and Muslims of Southern provinces got themselves completely cutoff from the larger Malay community on the other side of the border in Malaysia. This led to increasing tension and mistrust between the centre and the Southern province. Malaysia maintained its support to the Malay community and raised their issues with the Thai government. The low-level insurgency and violence intensified since 2001 when the Thai government started taking strict actions against the separatist groups based in the Southern province of Pattani. The Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra led government’s approach of dealing the region with massive force was not approved by a section of Thai military which overthrew the elected government in 2006. Since then, political dialogue and development centric approach is being exercised.

During the rule of Thaksin Shinawatra,the insurgent groups had expanded their use of violence against civilians in Thailand’s southernmost provinces of Pattani, Yala and Narathiwat, and in Songkhla. Over 7,700 were killed and thousands were injured in that period. In 2006, martial law was imposed on the region. The Thai politics grew impatient of Shinawatra’s hawkish approach and criticism against his use of force grew.

The Thai insurgent groups have no track record of having formal or informal linkages with international terrorist groups such as Al-Qaida of ISIS. The Thai insurgents have no direct experience of having participated in any transnational terror activity or a conflict such as in Afghanistan Jihad of 1989. The main terrorist groups who advocate the use of violence and have been involved in many terrorist attacks are Barisan Revolusi Nasional-Koordinasi (BRN-K), Runda Kumpulan Kecil (BRN-K’S military arm), Pejuang Kemerdekaan Patani (which has links with BRN-K), GMIP (Gerakan Mujahidin Islam Patani) and PULO.

Major attacks in Thailand

- On 10 March 2019 a number of small explosions occurred in Satun city and in Patthalung province in the south of Thailand.

- In December 2018, there were a series of small explosions on Samila beach in Songkhla city.

- In April and May 2017, there were several explosions in Bangkok.

- In August 2016, there were multiple explosions and incidents in tourist areas across Thailand, involving improvised explosive devices (IEDS) and incendiary devices.

- A large bomb exploded at the Erawan shrine in Bangkok in 2015, resulting in numerous casualties, including the death of a British national.

Barisan Revolusi Nasional-Koordinasi (BRN-K) or BRK is considered to be the most ferocious militant groups. It takes its inspiration from the Gulf based Islamist groups and intellectuals of Salafi or Muslim Brotherhood background. Pejuang Kemerdekaan Patani fighters are mainly based in villages and operate more independently. Another group Gerakan Mujahidin Islam Patani (GMIP) like BRN-K, became more violent after 2001 and became closer to Al-Qaida, though not formally linked with it. Barisan Bersatu Mujahidin Patani (BBMP) became very weak and disbanded after its key leaders were arrested in 2004.

In March 2005, the National Reconciliation Commission was established and assigned to seek reconciliation with the Southern Muslim community. Since then, many peace initiatives were undertaken. On 28 February 2013, the government signed a peace agreement with Malay groups, mainly National Revolutionary Front (BRN) and National Security Council of the Thai government with Malaysia[21] as the main facilitator of the dialogue.

Due to government’s approach to initiate political dialogue, the crisis in Thailand could not turn into a full blown violent crisis attracting terrorists’ curiosity. The crisis remains a local crisis along with multilayer dialogue processes continuing since 2005. Malaysia’s role as a facilitator of the peace process has played a crucial role in putting pressure on the Malay militant groups to join the dialogue and reach a compromise instead of insisting on full independence from Thailand.[22]

Thailand and the United States have close anti-terrorism cooperation, institutionalized in the joint Counter Terrorism Intelligence Center (CTIC), which was reportedly established in early 2001 to provide better coordination among Thailand’s main security agencies. The U.S. central intelligence agency reportedly shares facilities and information daily in one of the closest bilateral intelligence relationships in the region.

Malaysia

Malaysia is a unique Muslim country with a multicultural and multi-confessional society. The official religion is Islam, with 61 percent Muslim population, but there are a significant number of Buddhists (20%), Christians (9%), Hindus (6%), and Chinese (3%) and other confessions. Once an Asian Tiger, Malaysia has already experienced a higher economic growth and development in its 19ties when most of the South-East Asian countries were still struggling. Under Prime Minister Mahathir Muhammad’s leadership, Malaysia had already bridged the gap of economic development within the Malaysian society. That is considered as one of the main reasons that Malaysia does not face any violent or organized militant insurgency. The country had accommodated Muslims of all denominations and sects to be part of power in Malaysia’ federal power structure.

Islam arrived Malaysia in the thirteenth century with Arab travellers and traders had headed towards the pacific islands. Once part of Kingdom of Singapore, King Parameswara is said to have accepted Islam and run away to Malacca to establish his own rule. Since then, Malacca thrived to be an economic and political heavyweight in the Southeast Asian region by the fifteenth century; Malacca was conquered by Portugal followed by the Dutch in 1641. In the late eighteenth century, the British Empire has established its rule in Malaya after the Sultan of Kedah entered an agreement with the East India Company. The modern Malaysia as a nation-state was born in 1957 with the Malay population divided in to many countries including in Singapore and Indonesia. As Malaysia started growing rapidly, its Muslim population has more exposure to the Islamic world and was inspired by the happenings of the Islamic world. The Islamic revolution of Iran in 1979, the Afghan war of 1989, the Arab-Israeli conflict and other conflicts had shaped the public opinion of the Muslim population. The extremist interpretation, mostly imparted by the Islamist groups based in the Arab world and Pakistan such as the Muslim Brotherhood and Jamaat-e-Islami. Malaysia has attracted Islamist and conservative politicians and asylum seekers from all over the Islamic world. Iranian influence in Malaysia has been on the rise for the last two decades.

Groups such as Kumpulan Militan Malaysia (KMM) have conducted a few attacks targeting minority groups in Malaysia. KMM is deeply inspired by the Iranian revolution and aim at overthrowing the Malaysian government and establish an Islamic rule in its place. The group however, failed to spread and the Malaysian intelligence has effectively curtailed its expansion.

Political Islam remains one of the strongest political forces in Malaysian politics since the country has been taking inspiration from South Asian and Iranian Islamists. Important Islamic intellectual works have been produced which include Gerakan Islam Kini (Islamic Movement Now) led by Fadlullah Clive Wilmot. The book presents both the Muslim Brotherhood and Jamaat-e-Islami as a role model for Malaysia’s Islamic revivalism movement. Most of the books of Syed AbulAlaMaududi have already been translated and published in Malaysian language and have been widely circulated across the Islamic circles of Malaysia. Similarly, the books of Muslim brotherhood related clerics such as Sheikh Yusuf al Qaradawi have been published in Malaya language.

Malays ethnic identity remains common emotional constituent Malays living across the countries of the region. This complicates Malaysia’s domestic politics as well as its regional politics. Neighbouring countries accuse Malaysia of supporting separatist sentiments among Malay ethnic groups.[23] This has often been exploited by Jemaah Islamiyah in Indonesia and KMM. Malaysia’s Special Branch (MSB) and Singapore’s Internal Security Department (ISD) had launched a massive operation to identify and detain the extremist elements influenced by or in contact with Al-Qaeda. The operation was decided after the KMM tried to rob a bank, a few weeks before the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre on 11 September 2001. Among other international groups that have made Malaysia as their networking centre are Palestine’s Hamas, Lebanon’s Hebzollah, and Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood.

Malaysia has one of the most effective counter-terrorism mechanisms in the region, in cooperation with regional and international actors. In April 2015, Malaysia introduced its counter-terror legislation The Prevention of Terrorism Act 2015 (POTA) and enacted it on September 1, 2015. The legislation was thought to be a response to the rise of ISIS, to keep an eye and neutralize threats from ISIS allowing the authorities to use preemptive measuresagainst suspected terrorists. It includes “restrictions and conditions” on suspects by watching their internet activities and social media behaviour. Among important measures Malaysia undertook to stop the infiltration of ISIS was the introduction of the National Security Council Act (NSCA), and strengthening the use of previous laws such as Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2012 (SOSMA). [24]

Singapore

Previously known as the Kingdom of Singapura, the country has remained a seat of major powers of Malacca. At the end of the 14th century, the kingdom was attacked by neighbouring kingdoms and the King of Singapura ran to Malacca where he founded a new kingdom. In between he accepted Islam and was called the Sultan. With the portugese, Dutch and British colonial incursions, the Sultanate weakened and finally collapsed. Singapore became the main port city of the colonial administration and a thriving trade centre where hundreds of indentured labourers were brought from Chinese and Indian colonies. The ethnic demography soon turned in favour of Chinese ethnic groups who appeared as the dominant group after Singapore was declared an independent nation-state, carved out from Malaysia. The Chinese constitute 76% of 5.4 million populations. Malay became a minority with 15% and Indians as the third major ethnic community with 7% share in population. Fifteen percent population practice adhere to Islam, the majority of them are Malay. Thirty three percent are Buddhists, 18% are Christians, 11 % Taoists and 5% are Hindus. Since its independence, Singapore has been administered as a city-state under strict administration of Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, who transformed the impoverished island into a trade, educational, and technological hub, with a 6 percent annual growth for several decades. The country is hosting nearly 7,000 multinational corporations from all over the world.

With such a crucial global profile, Singapore has to undertake extra measures to prevent radical threats. Since the rise of ISIS, in the first case of a foreign terror cell in Singapore arrested 27 Bangladeshi suspects in December 2015. These workers had allegedly developed some level of sympathy and support for “armed jihad ideology” of ISIS and Al Qaeda. They also were part of a closed religious group in which extremist ideas of Al Qaeda terrorists were being shared. This could be considered as a preemptive measure to stop terror threats in Singapore. The accused “shared jihadi-related material discreetly among themselves” during their weekly meetings, where they also discussed armed militancy and recruitment efforts. Among them, 26 repatriated to Bangladesh, 14 of them were sentenced to jail under Bangladesh’s anti-terrorism act.[25]Since the rise of ISIS, the number of individuals being radicalized through online extremist propaganda has increased. Indeed, online radicalization has become a growing area of concern for Singapore as authorities detained or placed a total of 9 people under restriction orders (RO) in 2016. Instances such as – 44-year-old Zulfikar Mohamad Shariff, Singaporean self-radicalized, glorified via violence on Facebook, encouraged Muslims to wage militant Jihad, and radicalized two other Singaporeans. Number of such cases showcases the radicalization of individuals in each respective country.[26] In its de-radicalization program, Singapore arranged a psychologist, a religious counselor and a social worker to the accused extremists who tried to reform them and bring them back to normal way of Islamic thinking. The government has allocated a budget for such suspects to support the terror accused detainees and their families, which included social, educational and community support. The de-radicalization program was designed to reintegrate the accused in mainstream society. Religious Rehabilitation Groups were set up in 2003 and had expanded with a network of volunteers, Islamic scholars and teachers. During the program, particularly on Jemaah Islamiya suspects, they found systematic indoctrination injected by distorted ideology in detainees.[27]

The Joint Counter Terrorism Center (JCTC) coordinates between multiple agencies and departments of the Singapore. Since 9/11, Singapore has increased intelligence cooperation with regional countries and the United States.Singapore’s Internal Security Act (ISA) “empowers the government to address threats to national security not just through preventive detention, but also other measures like the imposition of curfews to deal with civil disorder.”

Myanmar

Once known as Burma, Myanmar had been a diverse country of more than five hundred ethnicities and many languages, and politically part of British India until 1945. When the Japanese captured parts of Burma and the Rakhine region in 1942, Buddhist monks started expelling and displacing many Muslim communities, causing communal riots. Meanwhile, the British administration offered a Muslim National Area for Muslims when they recaptured the region from the Japanese in 1945. But the short-lived promise came to an end when Burma declared independence and the new Burmese administration started expelling all Muslim officers and employees in Burma in large numbers. Indigenous Muslims who had been in Arakan for over 500 years were treated as enemies, illegal immigrants. Since then underwent tyrannical military rules which have mismanaged the coordination and power-sharing among different ethnicities of the country resulting a prolonged civil war situation and ethnic conflicts between the ruling military elites and their allies against the marginalized ethnic groups, both Muslims and many non-Muslims. This also led to mass expulsion and disenfranchisement of Muslims of Rakhine region. This led to their forced migration to Bangladesh and other countries where many of the Rohingya Muslims were attracted to extremist ideologies and groups and eventually there emerged Rohingya militant groups aiming to fight against the Burmese military and the government. Myanmar had already been in ethnic conflicts but in later years it has initiated a dialogue process for peaceful settlement of conflicts except with Muslims of Rakhine.

One of the militant groups now active in Rakhine is an Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) earlier known as Harakah al-Yaqin formed in 2013. The government of Myanmar declared the group as a terrorist group in August 2017. The group leaders were found to have close linkages with Pakistan and Pakistan based extremist groups. The leader of the ARSA Attaullah Abu Ammar Jununi, for example, was born in Pakistan and grew up Saudi Arabia. In 2016, he appeared in a video claiming responsibility for the terrorist attack in 2016.[28] His group was implicated in another terrorist attack on 25 August 2017, which claimed 71 deaths. The ARSA in its propaganda materials aims to ‘Defend, Salvage and Protect’ the Rohingyas against state repression. ARSA claimed that they have been fighting on behalf of the Rohingyas. So far, the group is said to have carried out several terrorist attacks on the Myanmar’s military and government targets. On January 5, 2018, it used a remote-control mine to target Myanmar’s soldiers. In late November 2018, Hindu community leaders in Myanmar accused ARSA of warning Hindu refugees in Bangladesh not to return to Rakhine State. On 9 October 2016, hundreds of insurgents belonging to ARSA attacked three Burmese border posts along Myanmar’s border with Bangladesh, killing nine Burmese border officers.

As the Islamic States’ global influences expanded, both the ISIS and ARSA found an opportunity to cooperate and seek each other’s help to strengthen their network. In the fourteenth issue of IS propaganda magazine Dabiq, a Bangladeshi jihadist called on others to join him to help the oppressed Rohingyas and warned about an attack to Myanmar by IS militants in Bangladesh. Myanmar had to adopt a comprehensive counter-terrorism training package and plan with collaboration of (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime) UNODC, which emphasizing to implement a whole-of-nation approach to counter-terrorism.[29]On 4 June 2014, the bicameral union Parliament passed the country’s first Anti -Terrorism law. The law carries a minimum 10 years and a maximum of life imprisonment or the death penalty for acts of terror. But Myanmar’s claims of fighting against terrorism were contradicted by several international rights groups as well as intra-governmental bodies and global powers. In December 2018, the US House of Representatives approved a resolution declaring Myanmar’s military campaign against the country’s Rohingya Muslim minority a genocide and this resolution stressed the authorities to reach a sustainable solution. Organization of Islamic Cooperation, European Union and the United Nations has also demanded the Myanmar government to take back the expelled Rohnigyas and give me full citizen rights. The Myanmar government, with a strong backing of China has mostly defied these international demands. As a result, the Rohingyas living in refugee camps in Bangladesh are prone to petty crimes and some of them are also being radicalized or recruited by extremists groups according to several media reports.

Conclusion

The South-East Asia region has different anatomy of terrorist and radical groups, much different from the Middle East or Pakistan/Afghanistan based groups. Unlike Middle eastern groups, the South East Asian groups have emerged in a different political and cultural conflict that has its strong roots both colonial legacies and political rights. One of the important aspects that distinguish South Asian Muslims from the Muslim societies of the Middle East is that they have a prolonged historical and rich experience of plural living with non-Muslims. Moreover, majority of Muslim communities in the region has no ethnic linkages the Muslims of Central Asia or the Middle East; rather, they are mostly converted Muslims who have cherished their local cultures and language despite accepting Islam. By maintaining their local languages and culture, the Muslims of South Asia have maintained a respectful relationship with their past.

This, however, had started changing since the Afghanistan Jihad in 1989 attracted many of the radical elements from South East Asia to fight for Al-Qaeda. On their return, these individuals with hardened Islamic ideology, having strong roots in political Islam, started imagining themselves as part of global Jihad movement in order to establish an Islamic order as preached by Al-Qaida and later on by ISIS. The militant groups active in the region were normally fighting for autonomy as in cases of Thailand and the Philippines, but in the aftermath of Afghan Jihad, these groups found a global network in their support and found a supply chain for arms and fund, something that changed the face of radical groups in the region drastically. The rise of Indonesia based Jemaah Islamiya of Abu Bakar Al Bashir is one such example that has played a role of regional grid for all extremist groups in the region in order to support them. In the aftermath of the September eleven attacks in the United States, Indonesia came under immense pressure to rein Jemaah Islamiya and its leaders. Malaysia being an economic hub stayed cautious in allowing these groups to expand their influence in Malaysia. With two main Muslim countries being serious against terrorism the region became more successful in evolving regional cooperation against terrorism, a model difficult to evolve in other regions such as in South Asia or the Middle East.

The recent wave of radicalism has come with the rise of ISIS, a group that controls enough technical know-how in spreading its message through the internet, social media and non-traditional communication. The region was not ready for a threat such as ISIS and was not equipped with technical tools to filter and stop online threats. But the success of ISIS in recruiting a significant number of fighters from the region alarmed the governments forcing them to identify the vulnerability of social media and internet users to the ISIS propaganda and recruitment agents. This stage of radicalization needs more precise counter-radical approaches and more intellectual engagement with their population and particularly with the young population to keep them away from the ISIS propaganda. The happenings in the Middle East, such as the Arab uprisings have emboldened many of the groups of the regions to exploit the happenings in their favour and contact with radical groups of the Middle East. Their contacts with Syrian, Iraqi or Egyptian groups even with Iranian groups, has resulted in understanding the Middle East through their ideologies. The region has seen dramatic growth in anti-Saudi sentiments among many of these groups, a new development among radical groups’ ideological outlooks. This new wave of radicalization, coming through the Middle East-based terrorist groups, has challenged the local governments as well as the governments of the Middle East with whom the South East Asian states have maintained cordial historical and cultural relations.

[1]OECD (2019). Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China and India 2019 Towards Smart Urban Transportation page 2,https://www.oecd.org/development/asia-pacific/01_SAEO2019_Overview_WEB.pdf

[2] ISIL Radicalization, Recruitment, and Social Media Operations in Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines BY Nathaniel L. Moir , Prism,7 No. 1, PP 92-107

[3] ISIS in the Pacific: Assessing Terrorism In Southeast Asia And The Threat To The Homeland Hearing before the Subcommittee On Counterterrorism And Intelligence of the, Committee On Homeland Security, House Of Representatives, One Hundred Fourteenth Congress, Second Session, April 27, 2016, Accessed online URL: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-114hhrg22758/html/CHRG-114hhrg22758.htm

[4]Yasin, NurAzlin Mohamed. “Impact of ISIS’ Online Campaign in Southeast Asia.” Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 7, no. 4 (2015): 26-32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26351347.

[5]Mysticism is a spiritual belief stating that a connection can be obtained with God or the spirits through thought and meditation.

[6] Desai, Santosh N. (1970). “Ramayana–An Instrument of Historical Contact and Cultural Transmission between India and Asia”. The Journal of Asian Studies. 30 (1): 5–20

[7]Russian International Affairs Council (2018). “Islamic Extremism in South-East Asia” Accessed online 20 August 2019, https://russiancouncil.ru/en/extremism-asean

[8] Congressional Research Service (16 October, 2009).“Terrorism in South-East Asia”, Congressional Research Service, US Congress.

[9]Spencer, Robert (2005). “Scott Atran Interview with Abu Bakar Bashir”, First appeared on FirstPost, reappeared on JihadWatch, accessed online 20 August 2019, https://www.jihadwatch.org/2005/10/islam-cant-be-ruled-by-others-allahs-law-must-stand-above-human-law-there-is-no-example-of-islam-and

[10]Teslik, Lee Hudson (2006), “Profile of Abu Bakar Bashir” 14 June 2006, accessed online 20 August 2019, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/profile-abu-bakar-bashir-aka-baasyir

[11]Congressional Research Service (16 October, 2009).“Terrorism in South-East Asia”, Congressional Research Service, US Congress.

[12]Congressional Research Service (16 October, 2009). “Terrorism in South-East Asia”, Congressional Research Service, US Congress.

[13]Habulan, A., Taufiqurrohman, M., Jani, M., Bashar, I., Zhi’An, F., &Yasin, N. (2018). Southeast Asia: Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand, Singapore, Online Extremism. Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses,10(1), 7-30. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/26349853

[14]Arianti, V., Avila, A., &Sim, J. (2011).Southeast Asia Country Assessments. Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses,3(1), 5-13. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/26350956

[15]USAID(2016). “Indonesian and Malaysian Support for The Islamic State”, (6 January 2016). Accessed online 20 August 2018, https://www.globalsecurity.org/ military/library/report/2016/PBAAD863.pdf.

[16]Yasin, N. (2015). Impact of ISIS’ Online Campaign in Southeast Asia. Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses, 7(4), 26-32. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/26351347

[17] Miller, Jack (2018). “Religion in the Philippines”, https://asiasociety.org/education/religion-philippines

[18]Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies (IDSS) (2006). “Terrorism in Southeast Asia – The Threat and Response”,Seminar report of international seminar organised by IDSS and US State Department in Singapore on 12 and 13 April 2006, accessed 20 August 2019, thhttps://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/NEW_TerrorismSEAConference0513.pdf

[19] The Fox News (28 July 2014). At least 21 Filipino villagers killed in attack by Islamic militants https://www.foxnews.com/world/at-least-21-filipino-villagers-killed-in-attack-by-islamic-militants

[20]Congressional Research Service (16 October, 2009).“Terrorism in South-East Asia”, Congressional Research Service, US Congress.

[21]Funston, J. (2010). Malaysia and Thailand’s Southern Conflict: Reconciling Security and Ethnicity. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 32(2), 234-257. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41756328

[22]Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies (IDSS) (2006). “Terrorism in Southeast Asia – The Threat and Response”, Seminar report of international seminar organised by IDSS and US State Department in Singapore on 12 and 13 April 2006, accessed 20 August 2019, thhttps://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/NEW_TerrorismSEAConference0513.pdf

[23]Helfstein, Scott (2018). “Radical Islamic Ideology in South East Asia”, Southeast Asia Project, The Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. https://ctc.usma.edu/app/uploads/2010/08/Southeast-Asia-Report.pdf

[24] Counter Extremism Project (2017). “Malaysia: Extremism & Counter-Extremism”, accessed online 20 August 2018, https://www.counterextremism.com/countries/malaysia#domestic_counter_extremism

[25]Kam, Stefanie. “Singapore.” Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 8, no. 1 (2015): 37-41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26369563.

[26]An, Fan Zhi, and Remy Mahzam. “SINGAPORE.” Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 9, no. 1 (2017): 30-33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26351480.

[27]Nasir, Amalina Abdul (2018) “How Singapore keeps terror at bay” accessed online 20 August 2018, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2018/06/09/how-singapore-keeps-terror-at-bay/

[28] The Guardian (November 18, 2016). “‘It will blow up’: fears Myanmar’s deadly crackdown on Muslims will spiral out of control” accessed online 20 August 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/nov/18/myanmar-deadly-crackdown-muslims-rohingya