Author: Julia Ebner

Number of pages: 210

Publisher: I.B Tauris & Co.Ltd, 2017

Reviewed by: Jumana Manasrah

In her book The Rage: The Vicious Circle of and Far-Right Extremism, Australian scholar and author Julia Ebner, a specialist in terrorism and extremism, highlights the development of extremist Islamists as well as the rise in the early 21st century — and studies the interaction between them.

Ebner says that some people call this age “the age of Putinism” or “the Era of Trumpism,” while she calls it “the age of anger.” This characterization stems from her belief that anger is spreading everywhere in our time. She points to growing hatred and violence in the world, high levels of crime, increasing security challenges, and the vast growth of the extreme right and jihadist organizations. Although witnessing major developments in terms of education, health, technology and development, the world, she writes, is one step away from total chaos.

The writer expresses concern about the rise of nationalist and populist movements: “I’m afraid humans will never be capable of learning from history, not even from the darkest chapters that struck the whole world not long ago.”

On May 2, 2011, millions of Americans celebrated after U.S. Special Forces killed Osama bin Laden. They had been waiting for this moment — ending a 13-year manhunt — which had begun prior to the attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon. Some celebrated, thinking that the world would be a “safer place” and witness the end of global extremism. Counterterrorism experts spoke of the decline of Islamist terrorist groups. Yet less than three years later, ISIS announced the establishment of its “caliphate.” By 2014, ISIS territory equaled the size of Britain, and by 2016 ISIS had recruited more than 30,000 foreign fighters. Apparently, the threat from Islamist extremism had never been truly weakened. It turned out that even if defeating a terrorist group temporarily stabilized a particular area by halting some attacks, the long-term threat posed by the global jihadist insurgency endures.

Mutual Anger

The book goes on to examine the interaction between far-right groups in the West and extremist Islamist groups. The far-right and extremist Islamist narratives – that Islam is at war with the West and the West is at war with Islam – effectively complement each other, she observes.

The writer opines that the first step in tackling extremism is to listen to extremists’ stories. Accordingly, she set out to interview both far right and extremist Islamist groups. The writer covered events organized by Hizb ut-Tahrir and the English Defense Association (ELD) in 2016. The speech she observed by the chairman of Hizb ut-Tahrir, Abdul Wahid, focused on issues that angered Muslims, referring to the oppression of Muslims in Kashmir and the rape of Kashmiri women by Indians, which he described as examples of the worldwide oppression of Muslims. He added that France had increased its discrimination against Muslims by banning students from wearing hijab, and pointed out that Germany had banned the niqab in schools. In the Netherlands, he added, some wanted to ban the Qur’an. In Australia, the One Nation party called for a ban on Muslim migration.

The writer observes that the style of discourse employed by Hizb ut-Tahrir leader Abdul Wahid was similar to that used by the EDL leader: The rhetoric of both focused on savage attacks by Islamists against the West, Western hostage issues, and the rape and humiliation of women. Both believe that war between the West and Islam is inevitable. The rhetoric and modus operandi of the ELD and Hizb ut-Tahrir are strikingly similar in that each incites hatred against the other. The crisis lies in their belief that the other is representative of its respective society as a whole.

The Rise of Global Jihad

The writer believes that in light of the global rise of far right and extremist Islamist groups, it is important to promote an understanding of the interaction between the two threats, which are often treated as unrelated by both analysts and politicians.

The writer discusses the origins of radical thought among Islamist groups. In this context, she draws attention to the legacy of Ibn Taymiyya, Abu Al-A’la Al Maududi, and the theories of Hassan Al Banna and Sayyid Qutb. The writer also addresses the rise of a new extremist Islamist wave, which she divides into two categories — violent extremist groups and non-violent extremist groups — noting that not all are jihadist. She also points to the existence of hundreds of extremist groups that do not call for jihad, and other jihadist organizations such as Al-Qaeda and ISIS. Regardless of whether the extremist Islamist groups are violent or not, the two types share the same goal of establishing the caliphate and the implementation of Sharia. They differ only in the way they seek to achieve their goals.

The writer traces the history of the rise of far-right ideas, referring to nationalism and fascism in the middle of the 20th century, anti-Semitism and Nazism, and the rise of hostility to Muslims and immigration since the 1980s. With regard to the rise of the new far-right wave in the world, the writer points to the spread of terrorist groups, in the decade after 9/11, where the US alone saw on average 337 right-wing extremist attacks per year. The US security sector, along with numerous American academics, consider these groups a threat to the safety of American citizens.

The writer believes that the extreme right is not a monolith, since the goals of right-wing movements and parties vary. Some are hostile to Muslims in general, while others focus on immigrants in particular and others still are focused on implementing national agendas.

The author believes that the rise of the right was caused by chaos, the media, the influx of immigrants and refugees, and other factors that contributed to the transformation of Europe into “Eurabia,” the description used by the writer to express the transformation of the European continent into a Euro-Arab-Axis as a result of Arab and Muslim migration.

Identity Politics

The writer refers to social inequality: one percent of the world’s population has accumulated more wealth than the remaining 99 percent, and the gap continues to widen every day. Add to this economic decline, the rise in unemployment, and the increasing material insecurity of hundreds of millions of people in the world. These circumstances led to the global financial crisis of 2008, which exposed the downside of globalization. Other related problems include the Eurozone crisis, the Ukraine crisis, and the crisis of immigrants and refugees.

Long-term political and social instability in the Middle East and North Africa, and the deterioration that followed the Arab Spring, was in the author’s view a turning point. Large immigration waves led to the destabilization of the current value system and consolidation of ideologies. Thus, socioeconomic inequality has shaped identity politics and extremism globally.

Victim and Demons

The writer believes that far-right groups and extremist Islamist groups similarly adopt a narrative of victims and demons, The stories they tell are transmitted and amplified through the media. While history books shape the stories of the past, the media frames the stories of the present. The author believes that both movements have successfully capitalized on opportunities offered by the media in spreading their stories around the world.

In the same context, she discusses progress made in the transmission of stories from ancient times through word-of-mouth, painting on cave walls, papyrus manuscript writing, and eventually the printing of books. Current developments are making the transmission of stories easier, faster, and more far-reaching through old, new, and social media, by which anyone can spread their stories, real and imagined, and employ images and videos to make them appear more visceral. This is what extremist and terrorist organizations around the world have focused on.

Two Sides of the Same Coin

Two Sides of the Same Coin

The writer believes that all far right and extremist Islamist and terrorist groups share the same rigidity and inflexibility — a tendency to take their proof texts literally. And as the two target each other through their stories, the writer believes that they are “two sides of the same coin”.

An Eye for an Eye

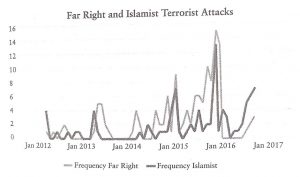

The writer indicates that the ratio of Islamist jihadist attacks to far-right attacks is one-to-one.

The author notes that attacks between June 2012 and September 2017 in the US, Australia, UK, France, and Germany seemed to occur almost simultaneously, based on data provided by the Global Terrorism Database, which records terrorist attacks across the world and includes information related to 150,000 terrorist attacks. The Counterterrorism Center found similar results at the very beginning of the twenty-first century, recording three peaks in far-right violence in the U.S. in 2001, 2004, and 2008.

Breaking the Vicious Circle

The author also believes that the “mutual hostility” between extremist Islamist groups and the far right has created a vicious circle of hatred, which leads to an increase in violence between the two sides, terrorist attacks, and further community divisions. The solution, she writes, lies in creating a strong common identity to bring together divided communities in order to force both parties to back down. She suggests encouraging critical thinking and creativity.