“Popular religion” draws life from local customs and traditions, and varies from one society to the next. Since its inception and spread, Islam, like other monotheistic faiths, has incorporated patterns of religious practices, rituals, and rites derived from the societies that embraced it. Culture, folklore, and popular sensibilities have left their lasting effect on the collective faith. It is hardly possible to speak of a “pure religion” in which rituals and doctrine are free of social influence and pre-monotheistic beliefs — whether in Judaism, Christianity, or Islam.

“Popular religion” draws life from local customs and traditions, and varies from one society to the next. Since its inception and spread, Islam, like other monotheistic faiths, has incorporated patterns of religious practices, rituals, and rites derived from the societies that embraced it. Culture, folklore, and popular sensibilities have left their lasting effect on the collective faith. It is hardly possible to speak of a “pure religion” in which rituals and doctrine are free of social influence and pre-monotheistic beliefs — whether in Judaism, Christianity, or Islam.

Yet as a scholarly matter, it is essential to distinguish between “popular Islam” and “traditional Islam.” Doing so means adopting suitable methods to study the various forms of individual, collective, and institutional interaction with religion — and recognizing the confluence of imagination, symbols, beliefs, and assumptions on the one hand and the normative construction of a given faith on the other.

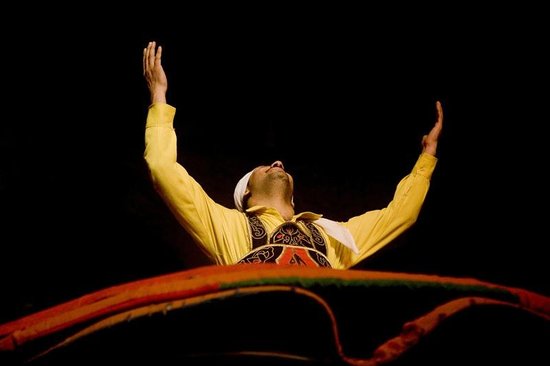

Al-Mesbar Center’s 138th monthly book, Popular Islam: Faith, Rituals, and Models, investigates the patterns of religiosity in contemporary Islam, and traces their transformation in response to political, economic, and cultural change. It integrates a reading of Islamic foundational references, such as the seminaries of Al-Azhar and Zaytouna, with seminal spiritual references, such as the awliyāa l-lahi (popular Islamic saints), dervishes, and legend. By focusing on widespread, fluid religious practices as opposed to fixed religious teaching, Popular Islam reinterprets texts through the prism of practice.

The practice of “popular Islam” encompasses the totality of religion and ritual, including birth celebrations, circumcision, shrine pilgrimage, mysticism, and belief. It is an unprompted and spontaneous practice. It lies beyond the control of institutions and can prove open to global culture and averse to confrontation.

Seeking to distinguish between religion and religiosity, this book adopts alternative rubrics, such as “behavioral mysticism” — a form of spirituality that attracts large masses of Muslims “without drowning them under piles of complex metaphysics.”

The growth of popular religiosity meanwhile influences Islamic clerical establishments, by competing with them for dominance of the religious space. It is typically more compelling to believers, because it is achieves greater intimacy.

The book includes a segment about popular Shi’ite religiosity, examining how the Ashura ceremony in Iraq changed following “the faith campaign” of the 1990s. Placing the reader in a historical context, it notes that Ashura became an official celebration under the Buyid dynasty of the tenth and eleventh centuries CE. It was later suppressed — a shift that contributed to Shi’ite-Sunni sectarian conflict. The In the Safavid era, the Ashura ceremony in Iraq took on exaggerated ritualistic dimensions, later prompting reformist movements to reduce the ensuing ritual excess. These movements found support in several influential scholars (“Mujtahidin” — notably Muhsen al-Amin (1867-1952), a leading Shi’ite cleric.

In addition to its coverage of Iraq, the book explores popular religion in Egypt, where Sufism looms large. This study highlights the connection between Sufism and the comparitively normative forms of Muslim religiosity, as well as the contribution Sufism made in Egypt to greater tolerance of other religions.

Turning to the subject of Sufi sainthood and shrine worship in southern Morocco, the book notes that the local saints include women (“Waliat”) as well as men. The study examines their biographies, with a focus on some of the more prominent among them. It also finds a visible decline in “Tariqa” (Sufi doctrine, literally the “path” of spiritual learning) practices in religious ceremonies, after a long history in which “awliyāa” were for many the axis of religion and daily life.

The book devotes two studies to Pakistan. The first explores the correlation of religion and power and its reflection on popular religiosity. The second introduces popular Islamic movements and groups in Pakistan, in which trends of violence reflect sectarian traditions and religious doctrines in the country.

Turning to contemporary popular religion in Turkey, the book considers two of its facets. The first is the range of religious ceremonies, such as Ashura, the celebration of the prophet’s birth (Mawlid al-Nabi), the commemoration of the “Isra and Mi’raj,” Ramadan, Eid al-Adha, and circumcision. The second study looks at the tombs of saints and other shrines, where visitors go to seek blessing or grace or just to mourn.

Finally, the book examines the ideological dimension of religion in Iran. The last chapter, concerns popular religion in Iran, as reflected by the teachings of Shams al-Tabrizi and his mystic interpretations of Qur’an and prophetic tradition.

Al-Mesbar Center would like to thank all the book’s contributors — in particular, our colleague Omar al-Bashir al-Turabi, who coordinated the team work.