by Armen Tsolag Marsoobian

As a child growing up in New York City, the little that I knew about the events of 1915 primarily came from two sources: my parents who were genocide survivors and my Armenian American friends. What I knew was simple enough. An ancient two-thousand-year-old nation had been ethnically cleansed from its historic homeland in what is now present-day Turkey. The few survivors were scattered across the globe in what has come to be known as the Armenian diaspora. Everything was black and white. Turks were the perpetrators and Armenians the victims. My parents, very young when the genocide began, survived due to luck and circumstance. Stories of survival seemed simple enough. I did not probe my parents further about what now seem anomalies from the familiar pattern of such survival stories. The genocide narrative was simple enough: All Armenians were rounded up in towns and villages, put on deportation caravans, and massacred on route or died from the rigors of their march into the Syrian desert. The few who survived either settled in the Middle East or emigrated to nations around the world.

Yet my parents’ story varied from this pattern. My mother’s father, a professional photographer, was spared from deportation because the Ottoman military and local government needed his skills. He was able to save his immediate family members who lived in Marsovan (Merzifon) but all the rest of his family in Sivas, Amasya, Samsun, Vezirköprü, and Trabzon perished. After the First World War my family attempted to restart their lives in Turkey but were eventually forced to leave due to the rise of Mustafa Kemal’s nationalists. First Greece and then the United States became their new homes.

My father’s story had an element that I found odd at the time but did not question. My grandfather had emigrated to the United States before the First World War but his wife and children were left behind in their village near Palu. The family survived the initial deportations due to the protection offered them by an Islamized uncle. This Islamized relative had converted many years earlier in order to gain release from the Sultan’s prison. He had married a Kurdish woman and was living in a remote mountain location. Eventually my grandmother and my father would make their way to Aleppo while two of his siblings perished on the journey. As with my mother’s family, my father would eventually settle in America where he met my mother and married.

Who was this Islamized Armenian relative, a man who played a crucial role in saving my father from certain death, yet a man never named and little mentioned again in family lore? I had always been taught that Christianity lay at the core of Armenian identity, an identity forged in 301 AD when the nation adopted Christianity. Christianity was central to Armenian survival over the course of nearly two millennia of domination by other peoples and empires. While I know very little about the role this Islamized relative played in my father’s story, I now know much more about the role of Islam in my mother’s story of survival. Strangely enough, I suspect that I know much more than my mother herself ever knew. This is the story I will tell you.

I begin with a photograph, one I first saw years ago when I was casually browsing through an old family photograph album. It was a strange photograph of people I did not recognize. Years later this photograph and the glass negative from which it derives, along with hundreds of others, came into my possession. Having learned from my mother the rough outlines of our family’s survival story, I had by then some appreciation of the context for many of these inherited photographs. Yet many details were missing. My mother, born in 1911, was quite young at the time of the genocide. Much of what she knew she learned from her parents and older brothers. Years later, after my mother passed away, I learned that she did not know many elements of their survival story and was probably kept in the dark about them. I learned of these beginning in 2009 when I starting delving into the large written record left by my surviving relatives. I will use this photograph to tell you a tiny portion of this story.

My sources for this story include a book-length memoir written by my great uncle Aram Dildilian and the transcript of a lengthy speech written by my grandfather, Tsolag Dildilian. Tsolag and Aram were brothers and had established themselves as photographers with studios in Marsovan, Samson, Konya, and Amasya. But the most important details were found in a memoir written by my grandfather’s niece, Maritsa Médaksian (née Der Haroutiounian), that had been recovered and edited by my cousin in Paris, Haïk Der Haroutiounian. For it was here that I came upon a startling discovery, an account of my family’s conversion to Islam and their adoption of Turkish identities. When I made this discovery I was shocked. I had been completely ignorant of this event. While my mother was too young to recall the conversion, her older brothers were certainly old enough to remember. One can only speculate as to why they chose to keep it a secret, a secret even from their own sister. No one in my generation knew this secret. I had in front of me a richly detailed day-by-day account of the events leading up to the August 10, 1915 conversion. Needless to say, this was not a voluntary conversion, for it was done under the coercive pressure of a violent and in most cases fatal deportation. From missionary accounts I learned that the date of August 10, 1915 coincided with a tragic date in Anatolia College’s history – the College for which my grandfather worked as a photographer. On this date the Armenian professors, staff, and students and their families, who had sought sanctuary on the campus, were forced onto the deportation marches that led to their deaths.

The months preceding this fateful day in August were marked with escalating fear and violence, the direct result of which was a mass conversion of Armenians to Islam. Combing a variety of sources, I have reconstructed an almost day-by-day account of those horrific spring and summer months of 1915. I cannot provide the full narrative here, though a published account in both Turkish and English should appear late in 2014. Instead, I will provide a short summary of my story.

The first stage of the genocidal process in Marsovan began on April 29, 1915. Political leaders of the Armenian community were arrested and soon sent off to Sivas for execution. On June 2 orders were given that all firearms and army deserters be turned over to the government. Many complied, especially after the urging of their religious leaders. Yet on June 26, upwards of 1200 males between the ages of 20 and 45 were arrested and jailed in the city’s military barracks. Among the detainees was Garabed Kiremidjian, whose personal and financial relationships with local government officials proved crucial in the negotiations regarding the fate of the prisoners. Kiremidjian first persuaded the prisoners to turn in whatever weapons they still may have had hidden in their homes. Soon he noticed that small chain-bound groups of detainees were being removed from the barracks at night. Having inquired with the gendarmes’ commandant, Mahir Bey, he was informed that these men were being deported to Aleppo. Kiremidjian eventually persuaded Mahir Bey to accept a “fee” of 50 liras to allow anyone who so desired to convert to Islam and thus escape deportation. First-hand reports of the cruelties witnessed in the barracks are contained in the family memoirs. The first mass conversions in Marsovan took place at the end of June and the beginning of July. Ironically Interior Minister Taalat Pasha had just ordered a halt to most conversions when he realized that too many Armenians were willing to convert in order to escape death, undermining the Committee of Union and Progress’s plan to reduce the number of Armenians to under 10% of each sanjak’s population. The official deportation orders for Marsovan were announce on July 4. While the numbers of converts may be somewhat exaggerated, Kiremidjian concludes that “about 3000 persons, wives, old ones, and children, were converted.” Kiremidjian then reports that the 10% rule was implemented and only the 1200 who had already paid the bribe could stay, while the remaining 1800 converts were deported. He further reports that a significant proportion of the Protestant Armenians converted while most Catholic and Orthodox Armenians refused to do so. By August, the only non-converted Armenians remaining in Marsovan were those on the Anatolia College campus and the surrounding neighborhood, including my family, the Dildilians and Der Haroutiounians. The leaders of Anatolia College had successfully bribed local officials to protect their Armenian staff and their families. All this hard work was for naught when the gendarmes finally entered the campus and deported the Armenians on August 10. My grandfather Tsolag was warned by Mahir Bey that the protection he was afforded could not continue without conversion. After much argument within the family and with the encouragement of Kiremidjian, the family converted on the afternoon of August 10th. With the conversion the stage is now set to return to our puzzling photograph.

Let me now ask some questions, some simple, others more difficult: When was the photograph taken? Where was it taken? Who is in the photograph? What are these people doing? What is the message these individuals are trying to convey in this photograph? The final question and the most important for our purposes is: How did these individuals come to be in this particular place at this particular time for this photograph to be taken?

The answer to the first question — When was it taken? — is established by the banner hanging on the wall behind them that reads in Armenian, “Ցիսռւս ծնավ, 1916” transliterated as “Hisous Dzenav, 1916.” This translates to “Jesus was born, 1916.” The individuals are celebrating Christmas, in this particular case, Armenian Apostolic Christmas, which is traditionally celebrated on January 6th. We know from accounts in Maritsa’s memoirs that her mother Haïganouch, pictured in the photograph leaning her head on her left arm, was a devote Apostolic, unlike her older brother Tsolag, who had adopted the Protestant faith. The memoirs mention that the first Christmas after the deportations was secretly celebrated in the Der Haroutiounian household, answering our second question as to where this photograph was taken.

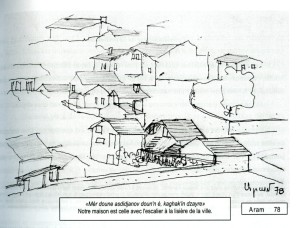

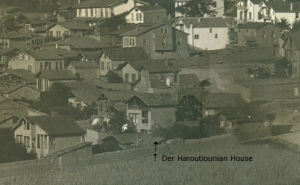

[Our house is one with the staircase near the edge of the city. Sketch of the Der Haroutiounian house drawn by Haïganouch’s son Aram over 50 years after being forced to leave his home. ]

[The Der Haroutiounian house in Marsovan at the edge of the city. Cropped from panoramic photograph after being matched to Aram’s sketch. Circa 1914.]

[Tsolag Dildilian’s home & studio (indented roof with glass) Anatolia College in background.]

Answering the third question – Who is in the photograph? – takes us directly to the topic of the individuals rescued by my family. The five males pictured are all relatively young men who would have been of draft age. Young males were called up for military service prior to the deportations. Conversion to Islam may have enabled one to avoid deportation but did not exempt one from conscription. Aram Dildilian, pictured in the back row on the right, had been allowed to convert to Islam and given the Turkish name Zéki (intelligent). As a youth he had his leg amputated, exempting him from military service. The four other young men pictured would be considered deserters at this point and would have been subject to arrest and immediate execution. Almost all Armenians serving in the Ottoman army had been disarmed and placed into labor battalions after Enver Pasha’s directive of February 25, 1915. By spring, many of these soldiers were being slaughtered en masse. The four young men in the photograph had been hidden in Haïganouch’s house since August 1915. Through various sources, we have been able to identify the four: Khatchadour Gorgodian (back row, second from left with the priest’s cap); Haïg Filizian (back row to the left of Aram with his hands on the shoulders of the man seated before him); Garabed Médaksian (the bearded man seated in front of Filizian); Lemuel Chirinian (seated below Médaksian, playing the musical instrument). Khatchadour, Haïg, and Lemuel had all been students at the College, while Garabed had been an instructor in the College carpentry shop. Here is a picture of Lemuel in his happier days:

The four other younger individuals in the photograph are four of Haïganouch’s five children.

The next question – What are these people doing? – has already been partially answered: Celebrating Christmas mass. In addition to the Bible and the cross that Khatchadour is holding are a number of objects that would be used in the mass, including a wafer and a glass of what appears to be water, a candlestick with the candle missing, and an incense holder. Could the missing candle, and possibly incense reflect the reality of their deprivations yet still symbolize their faith in persevering?

[Close-up from Christmas celebration photo showing the table items used in the mass.]

The family is documenting this Christmas celebration for posterity and simultaneously affirming their true faith, despite having outwardly adopted their oppressors’ faith. There may also be a political message here. The flag on the table has three horizontal stripes and two oblique bands with three stars in each. This resembles the flag of the Society of Armenian Students of Geneva:

Geneva was the center of diasporan Armenian nationalist activity in the 1890s. Both the Social Democrat Hunchakian Party (SDHP) or “Hunchaks” and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation or “Dashnaktsutiun” were active in Geneva, with the former being founded by Armenian university students. The photograph is thus a statement of resistance – resistance spiritually and in the name of the nascent Armenian nation.

We now come to the final question regarding this old photograph and the topic of the survival of Armenians in Marsovan: How did these individuals come to be in this particular place at this particular time? I will try to summarize how this came to pass.

Neighborhood by neighborhood the deportations continued from late June into July. At first Haïganouch expands the family hiding place, but after seeing her Armenian neighbors violently forced out of their houses she decides in July to move into her brother’s home across the street from the college. Her brother Tsolag had been exempted from the deportations by Mahir Bey. Tsolag had close professional and personal ties to the College. His brothers and children were students there. He was the college’s photographer, operated the hospital’s x-ray machine, and ran the stationery store concession.

As the deportations continued into July, the Armenian male students gradually became aware that the College could no longer protect them. Three of them, Hovhanness Sivaslian, Hagop Kayayian and Garabed Médaksian, close friends of Tsolag’s younger brother Aram, agree that when their time came for deportation, they would escape to the remote mountain countryside of the Greek village of Galinsin. A Greek classmate of theirs, Andrias, had agreed to help them once they reached their destination. Their plan was to live off the land and “rough it” through the autumn and winter, hoping that by spring the Ottoman armies on the collapsing Russian front would be defeated. Earlier they had buried rifles, ammunition, and hatchets in hiding places on the campus. They would use these rifles to live off the land by hunting but they soon realized that their access to these weapons would be cut off once the deportation began. It was also illegal for an Armenian to have a weapon at this time. They obtained a promise from Aram that once the campus had been cleared, he would return and smuggle the weapons across the street to his brother’s house. They would attempt to break off from the deportation caravan and return to collect their supplies.

The fateful day of the deportation of the Armenians from the College arrived. August 10, 1915 has been described in detail in the missionary accounts, especially in the White, Compton, and Morley works referenced earlier. There are also detailed accounts in the memoirs of Aram and Maritsa as to what transpired on the campus and its environs that day. Early that morning, Aram was working in one of the joinery shops on campus. Mr. Getchell, the college dean, warned him of the arrival of the gendarmes who had come to deport the Armenian professors, staff, students and their families. He is advised to run home to Tsolag’s house across the street. He slips out through the “professors gate” and returns home. A similar account is given by Maritsa. The families gather on the top floor of the house and watch in disbelief as the Armenians along with a few of their belongings are loaded onto oxen carts and marched off into the countryside. The upper floors of their house provide a good vantage point for observing the activities on campus and in the surrounding residential neighborhood.

[Tsolag Dildilian’s family home across the street form Anatolia College. The family observed the deportation of the Armenians from the upper floors of this house.]

[Tsolag Dildilian’s family home across the street form Anatolia College. The family observed the deportation of the Armenians from the upper floors of this house.]

Aram comments: “It was a tragic scene for us to watch . . .. One by one all the oxen carts came out of the main gate where soldiers with bayonets on both sides . . . watched them closely . . . all our dear and able professors, teachers with their wives and children and all the college students and other workers . . . With tearful eyes, we watched them go one by one, our last hope of the survival of our nation’s cream . . .”

[Oxen carts used for their original purpose of the harvest of grain not of people. Marsovan plain, circa 1913.]

This theme of the “survival of the nation’s cream” clearly motivates Aram and his family in their efforts to rescue the few Armenians who manage to avoid or escape the deportations. These educated young men and women of Anatolia College, who are hidden by the family for upwards of two years, provide the hope that the nation will be reborn once the war ends.

These endeavors of rescue and refuge begin almost immediately. The promise that Aram had made to his college friends, Hovhanness, Hagop, and Garabed (Garo) had to be kept. The three friends would make an attempt to escape from the deportation caravan, return to Tsolag Dildilian’s house in the cover of darkness, be provisioned with supplies, and make their way to the nearby mountains. Late on the night of August 10th, the young men arrive at my grandfather’s house and are temporarily hidden in a neighbor’s abandoned wash house. Aram’s memoir describes the lengths to which he went in order to secretly bring the weapons from the College back to his friends hidden next door. Tsolag and his wife Mariam supply the men with food and blankets and they set off to the mountains. Aram keeps in touch with them through a go-between. Even providing them medicine when one of them falls ill.

The story of their escape is told to the family and recorded in both Aram and Maritsa’s memoirs. The young college men escaped the deportation caravan when it paused at a monastery just outside of town. While resting at the monastery they are asked by an Islamized Armenian to help repair some broken farm equipment. They take the opportunity to hide and with the assistance of a friendly neighborhood Turkish policeman, Ipék Agha, they made their way back to my grandfather’s house.

Maritsa’s memoir contains an emotionally upsetting account. Garabed’s caravan also included his mother and sisters. For practical reasons the plan of escape and mountain refuge could not include these women, and Garabed is forced to leave them to their fates. Garabed’s mother gives him her coat and one of his sisters gives him her christening medal to sell in order to pay for his survival. Maritsa writes:

“Garo and his companions then go and hide amidst the wheat stalks. Some moments later, the transportation caravan sets out and, when his mother and sisters, walk past him, Garo wants to rush forward, but his companions hold him back because their hiding place would have been revealed. And anyway, of what help would he have been to his mother and sisters? He would have been executed before the caravan reached the Field of Irises. This was a vast spread of land covered with blue, white and yellow irises.”

This was the last time that Garabed saw his family. No one knows when or where they perished. One can only wonder if it took place in that field of blue, white and yellow irises.

Winter in the mountains proved unbearable for these young men and they eventually returned to my great aunt Haïganouch’s house, where Aram had enlarged the secret hiding place. This is how Garabed Médaksian came to find himself in that Christmas celebration.

Upon the arrival of the four young men, Aram began building a secure permanent hiding place:

“We built a very safe and comfortable underground hiding place in two sections so that in case one section is found, the back section will be safe . . . I made a fresh-air ventilation [system] and there was room enough for 8 persons. . . . I put up a watchtower with mirrors to look and see in every direction so that the lookout … would signal the boys to go down in case of suspicious people.”

More easily detectable hiding places were made around the property so that if police searches found these “fake” hiding places empty, they would then assume that no one was hidden in the house. Secretly at night they increased the height of the family compound’s outer walls by adding sunbaked bricks.

Soon the four hideaways were joined by Khatchadour Gorgodian, the second of the four men in the photo, along with his brother, who had hidden themselves in a nearby abandoned house. Now six young men were hiding in the house but the story does not end here, for more were yet to come. Aram describes the arrival of Lemuel Shirinian, a classmate and talented musician related by marriage to his older sister Parantsem – a sister who would perish in the deportations. Lemuel had been hiding on the campus until the College’s president, George White, ordered him to leave. Aram continues: “Later, we got in Haroutune, who was hiding by himself at Marderos’s silk factory and then Mihran trying to hide himself here and there, and Haïg Filisian (who) managed to hide himself in the college attic room . . . Now we had 10 men, too many to keep in one place and too dangerous for safe keeping…” Eventually eight young women from the Anatolia Girls’ School who feared being taken into Turkish families as brides would join them, requiring a further expansion of the hiding places. With Haïganouch and her 5 children total of 23 people were living in the household at one point.

At the same time that Aram and Haïganouch were hiding these young people an unknown number of young men were hidden at my grandfather Tsolag’s house near the College. Many years later, my mother would recall the sudden appearance and disappearance of young men in the household. No adult would acknowledge their presence, making her wonder if she had seen apparitions. Neither Tsolag nor Haïganouch knew the details of each other’s activities in hiding these young people. A mutual ignorance may well have been a safety strategy. The less one know of each other’s activities, the less the likelihood of a coerced betrayal of each. We have now solved the mystery of how these four young men, Garabed, Khatchadour, Lemuel, and Haïg came to be in that old photograph of a Christmas celebration – a celebration, ironically, taking place in a household of ostensibly “Islamized” and “Turkified” Armenians.

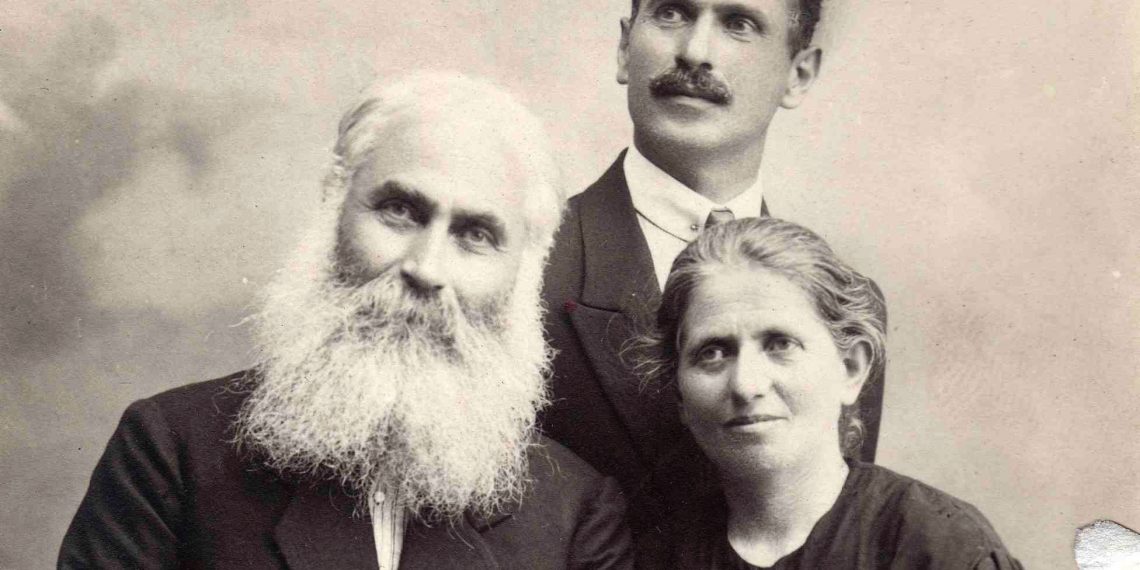

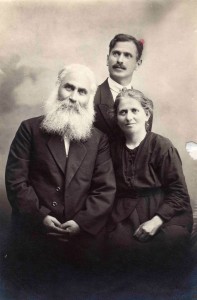

I would like to conclude my story not with words but with an image. The heroes of this story are Tsolag, Aram, and Haïganouch, three siblings who risked their lives to save their fellow human beings and whose heroism has never been fully recognized.

[Tsolag with beard on the left, Haïganouch on the right and Aram standing in the back.]

The writer is Chairperson and professor in the Department of Philosophy, Southern Connecticut State University.