The teaching of philosophy in the Arab world faces a double problem. The first relates to the fact that educational planners’ interest in philosophical studies has declined in schools and universities in favor of natural and mathematical sciences, or sciences with a practical application. The second is fear of including philosophy courses in educational curricula in secondary schools, especially in a number of Gulf countries. This fear is due to accusations that philosophy threatens Islam and faith, as well as the fear, by political elites, of the philosophy’s capacity to build a critical and questioning mind — the opposite of a submissive mind.

The teaching of philosophy is prohibited in Saudi Arabia. The justification for the ban is presented in the context of views of Shaykh al-Islam Ibn Taymiyyah on philosophy, or from ideological writings by Hanbali Salafis. This prohibition is based on several fatwas. According to a fatwa issued by the Permanent Committee for the Scholarly research and Ifta, “It is not permissible for a Muslim to study philosophy, manmade laws, etc., if he does not possess the capability of distinguishing truth from falsehood, lest they should deviate from the straight path. It is permissible for those who are able to digest and understand it after studying the Qur’an and Sunnah, to study it with the intention of distinguishing between the right and wrong in them, and establishing the truth and abolish falsehood, as long as this will not distract them from the more important purpose of the Shari`ah. Accordingly, it should be known that it is not permissible to make the teaching of philosophy a general field of study in schools and educational institutions. In fact, it should be studied by qualified specialized Muslims who take it as an Islamic duty to defend the truth and refute falsehood.”

On the other hand, there are many academic and elite voices in Saudi Arabia who have called for the teaching of philosophy in secondary schools and allocating sections for philosophy in Saudi universities. In addition, some cultural centers hold cultural activities allocated to philosophy, especially the “Literary Club in Riyadh,” which founded the “Riyadh Philosophical Circle,” aiming to hold cultural activities twice a month and discuss philosophical papers.

The crisis of philosophy, in terms of teaching and production, is not limited to Arab countries. The French philosopher Régis Debray talks about the “erosion of old frameworks to transfer meaning and the decline of interest in classical human studies and literary disciplines which witnessed the superiority of visual media and a new demographic distribution in educational institutions.” He also refers to a pattern of formalized technical approaches to school texts and cultural effects, which, more or less, marginalized“disciplines of old meaning” (literature, philosophy, history and art). (See Tajarub Kawniyyah fi Tadris Al Adyan – Universal Experiences in the Teaching of Religion, translated and edited by Mohammad Haddad et al, Al Mesbar Studies and Research Center, 1st ed., 2014).

In her book “Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities,” American philosopher Martha Nussbaum warns against the “silent crisis” that humanities (including philosophy) is facing in Western societies due to “radical changes in what democratic societies teach the young.” She says: “The humanities and the arts are being cut away, in both primary/secondary and college/university education, in virtually every nation of the world. Seen by policy-makers as useless frills, at a time when nations must cut away all useless things in order to stay competitive in the global market, they are rapidly losing their place in curricula, and also in the minds and hearts of parents and children,” in order to enhance skills and sciences that suit the profit motive. (See Martha Nussbaum, Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities, translated by Fatima Shamlan, HEKMAH, 16 September 2016).

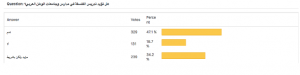

The above lines come in response to a survey conducted by the Al Mesbar Studies and Research Center on its website: “Do you support teaching philosophy in the schools and universities of the Arab world?” The survey started in January and ended in mid-February 2018, and respondents were presented with three choices: “Yes”, “No,” and “I accept under conditions.” 699 persons responded to the survey as follows: 329 said Yes (47.1%); 131 said No (18.7%); 239 said I accept under conditions (34.2%).

Survey Results (January – mid February 2018)

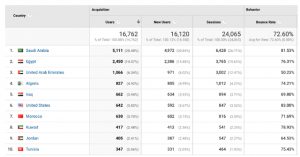

The results of this survey can be read in several ways. Numerically (i.e. number of participants), there is no significant difference between supporters (329 or 47.1%) and supporters with conditions (239 or 34.2%). However, the refusal of 131 respondents to accept the teaching philosophy is a negative indicator. Considering the refusal from the viewpoint of supporters with conditions allows us to assume that respondents who accept under conditions have implicit restrictions regarding teaching philosophy in schools and universities. Thus, respondents who chose “No/with conditions or restrictions” constitute the majority. Although it is difficult to identify the age groups that participated in the survey, they are likely to be from the younger and middle-age groups. It should be noted that visitors to the Al Mesbar website (most visitors in the past three months come from Saudi Arabia, followed by Egypt, the UAE, Algeria, and Iraq) have ideological, scientific and research backgrounds, and are interested in the phenomenon of Islamism. This is because Al Mesbar gives priority to covering Salafi, political, and jihadist movements in its monthly books and publications.

If survey respondents who answered “No” (131 or 18.7%) are of an Islamist orientation, then the “No” response is unsurprising: The Islamist mindset is opposed to philosophy and even reason, due to the takfiri principle, “Following logic leads to hidden atheism.” An article entitled “The Philosophy Curriculum and the Generation of Loss” by Rashid Al Ghannushi attacks philosophy as follows: “Philosophy did not only fail to provide solutions to the problems Tunisians encountered, but also constituted an element of sabotage, destruction, and disorientation of both individuals and society.” Al Ghannushi calls for replacing the texts of Al-Kindi, Al-Farabi, Ibn Sina, Ibn Rushd, and al Qadi Abdul-Jabbar with texts of Islamic thinkers, such as Hassan Al-Banna, Sayyid Qutb, and Al-Mawdoudi. He considers that teaching philosophy as practiced in all Tunisian institutions is like throwing our students “into the valley of loss, confusion and cultural dependence.” Al Ghannushi believes that teaching Marx, Freud, and Sartre in the Tunisian philosophy curriculum is a disaster for younger generations, and criticizes the Islamic philosophy curriculum, which spreads some of the Mu’tazilite views. (See Mohammad Al Mazoughi, Mantiq al Muarrikh: Hisham Djait: al Dawla al Madaniyya wa al Sahwah al Isamiyya — Logic of the Historian: Hisham Djait: Civil State and Islamic Awakening — al Jamal Publications, Beirut, 1st ed., 2014, pp. 169-170-172; See, quoting Al-Mazoughi: Al Ghannushi, Rashed: ” The Philosophy Curriculum and the Generation of Loss ” in Maqalat (Articles), Islamic Movement publications, 1984).

Table of visits of Al Mesbar website by countries in the past three months

Returning to our survey, we propose a second hypothesis concerning the “No” response. If respondents do not follow an Islamist orientation, the “no” indicates a lack of awareness regarding the importance of teaching philosophy in schools and universities of the Arab world. It is an attitude epitomized by the slogan, “Islam does not need philosophers,” meaning that religion is based on absolute truth, and philosophy by its nature stems from pluralism and criticism. We cannot overlook the negative residue left by a number of imams and muftis concerning philosophy in classical and contemporary Islamic history, such as Ibn al-Salah Al- Shahruzuri [d. 643 AH], who issued a fatwa forbidding philosophy and logic. From this fatwa calling for the abolition of reason, Imam Ahmad bin Atta Allah Al Sakandari (1260-1309) derived his argument to “abstain from rational calculation.” Al- Shahruzuri says in his fatwa: “Philosophy is the basis of abomination and disintegration. Those who think like philosophers cannot see the virtues of the purified Shari’ah. As for logic, it is the entry point of evil, and the entry point of evil is evil; its teaching and learning is forbidden by the Lawgiver… The use of logical terms in the discussion of legal provisions is a hateful evil and heretical innovation, since following logic leads to hidden atheism.” (See: Al Sakandari, Ahmad bin Atta Allah: al-Tanwir fi Isqat al-Tadbir — The Book of Illumination — edited by Mohammad Abd al Rahman al Shaghoul, al-Maktabat al-Azhariyyah lil Turath, 1st ed., 2007).

The results of the survey on the teaching of philosophy in schools and universities of the Arab world do not appear to be encouraging, even though supporters constitute the highest ratio (329 respondent or 47.1%). There is no doubt that this survey reflects, largely, the plight of teaching philosophy, which witnessed a dangerous decline in recent decades in most Arab countries. For example, in the United Arab Emirates, philosophy is not currently taught at the secondary level (official high schools). It was abolished in the late 1990s by a decision of the Ministry of Education, after being taught in “philosophical thinking” and “logical thinking” (literary section) courses. Some of the topics related to philosophy in the twelfth grade are included in the psychology course where materials such as “critical thinking skills” and “creative thinking skills” are offered to students. (See: Halat Tadris al Phalsapha fi al ‘Alam al Arabi — The State of Teaching Philosophy in the Arab World — Group of Researchers, supervision: Afif Othman, coordination, Rita Faraj, International Center for Human Sciences, Byblos, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2015).

Teaching philosophy in Arab high schools and universities in general, and Gulf high schools and universities in particular, is urgently needed for its two potentialities. First, it helps build critical and conscious minds open to the world and a multiplicity of perspectives and opinions, especially during adolescence, where many questions about humanity, religion, God, and existence are raised. Second, by consequence, it can help fight radicalization, religious violence, fundamentalism, and terrorism, because philosophy is inherently anti-fundamentalist and anti-absolutist.

Why should we teach philosophy in our schools and universities? Three issues make this necessary. First, philosophy is against violence, fundamentalism, guardianship, and absolute judgment. Second, critical thinking is a virtue, and must be imparted to young people in our region. Third, philosophy is a human necessity, because it helps people find contrastive meaning in their lives in an overwhelmingly complex world.

Lebanese researcher Rita Faraj is a member of the Editorial Board of Al Mesbar Studies and Research Center.