by Diana Galeeva

This material was originally presented at the Eighth Gulf Research Meeting (GRM), 1-4 August 2017, which was organised by the Gulf Research Centre at the University of Cambridge.

A piece of news announced on the morning of the 24th of June 2016 continues to be one of the most controversial subjects in world politics. On Thursday 23rd June, the UK decided by referendum to leave the European Union, with the ‘Leave’ campaign claiming a majority of 52 percent of the vote. This historical decision on the part of Britain is one on which rests not only Britain’s own future, but also that of the development of the European Union as a whole. After the vote, Europe was divided over the decision to remain in or leave the union. It became one of the central issues in the recent Dutch, French, Germany elections, and will be discussed in following elections across Europe. As well as by some countries in Europe, the British decision was supported by some of the GCC states, especially Oman, and this spread the rumours and discussions about the future of another international organization – the Gulf Cooperation Council (the GCC). Moreover, the current 2017 GCC crisis (Qatar, on the one side, and Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain, on the other) has brought a new wave of uncertainty over the nature of cooperation between the GCC states. Considering national identity as a key contributing factor to the Brexit vote, this paper will focus on the question of how the concept of national identity has helped to weaken or strengthen relations between the members of the EU and the GCC. Further, it will propose that recognising the shared identities of GCC states will be crucial for preserving the unity of the GCC.

Drawing on an examination of liberalist and constructivist theories about how collaboration and peaceful relations between states are built and maintained, this paper argues that the liberalist school of thought does not adequately describe the development of international organizations such as the EU and the GCC. It is the liberalist argument that worldwide institutions are key to ensuring cooperation between states. The development of these institutions should be considered in accordance with the constructivist approach, which takes into consideration strategic cultures, and the importance of norms and identities. This article will focus first on the debates between liberalists and constructivists; second, it will examine the European Union, taking Brexit and the French elections as case-studies; and finally, it will observe GCC politics, using Oman and Qatar as examples.

Liberalism and Constructivism

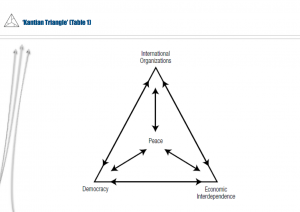

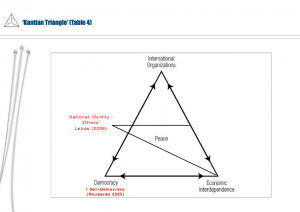

In order to explain the current dynamics of the EU and the GCC, and to suggest the future of these organisations, this paper focuses on the differences between two leading schools of thought in International Relations (IR) theory: liberalism and constructivism. Representatives of the liberalist school believe that global institutions play the main role in ensuring cooperation between states (Shiraev, 2014). Kant’s ideas (1795) provided a foundation for the development of liberalism. These ideas developed into the ‘Kantian Triangle’ (Table 1) (Russett, 2013) and can be characterized as follows: democracies will refrain from using force against other democracies; economically essential trade generates motivations to maintain peaceful relations; worldwide organizations can oblige decision-makers by positively promoting peace.

The Kantian Triangle suggests that countries which embrace democracy, the first element in the triangle, will rarely fight or threaten each other. Democracies are also more peaceful in their interactions with other states; this is the base of democratic peace theory. According to Kant (1795), there are two explanations for why democracies do not fight each other: norms and institutions. Considering norms, he explains that democratic peoples and their leaders acknowledge other democracies as functioning under similar principles in their domestic relations, and so extend to them the principle of peaceful conflict resolution. Moreover, considering institutions, democratic rulers who fight a war will have responsibility for its losses or costs in the aftermath of war. Democratic societies will also expect non-democracies to make threats and use force, preventing their peaceful development. By contrast, Rousseau, (2005) in Democracy and War, used the case of Saudi Arabia to demonstrate the restrictions of democratic peace, stating that non-democracies can also act peacefully with their neighbours due to domestic political constraints.

The second element of the Kantian triangle is economic independence. Continued commercial collaboration becomes a medium of communication whereby information about preferences and needs is swapped across a comprehensive range of issues ranging well beyond the particular commercial exchange. The larger the contribution of trade between the states in their domestic economies, the stronger the political foundation between them, and the more beneficial the maintenance of peaceful relations becomes. Russet (2013) explains the idea further, saying that trade and peace are reciprocally related. Democracies trade more with each other, considering that trade agreements are likely to be preserved, and international property rights are respected with well-known legislation. As a result, trade usually promotes common prosperity that preserves the development and stability of democracy.

The third element of Kantian triangle is International organizations. International organizations include both universal organizations, like the United Nations (UN), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and those focussed on specific types of states or regions. Regional organizations, such as the European Union and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe are essential because they are composed mainly of democracies with a variety of powerful incentives and penalties to attract new member states, which would like to be democratic. International organizations, which mainly consist of democracies, are very effective in keeping peace among their members. However, as Russett (2013) explains, economic shock, such as a global depression, can immediately negatively affect a union. The immediate consequences are in trade and finance, leading to economic failure and global conflict. It would be harder for international organizations to guard free trade, and democratic governments fall – as happened during the economic depression in the 1930s. All of this could lead to international conflict and war.

The main idea of the Kantian Triangle, and the core of IR liberalism, is democratic peace theory: the idea that democratic states develop peacefully, and non-democratic states, non-peacefully. In contrast, critics consider non-democratic states to also be able to peacefully develop (Rousseau, 2005). For international liberalization it is important that states are internationally economically interconnected. Thirdly, international organizations and institutions, such as the UN, NATO and the EU, can maintain cooperation among states. However, if economic relations determine the union, institutions can also fail. One of the main factors cited by liberalists as leading to unsuccessful development is economics. Other factors were not considered, and national identity was not considered at all.

Constructivism

In opposition to this school of thought, constructivists argue that global political relations between countries are socially constructed (Friedberg, 2005: 34). In other words, states’ relationships are based on three categories: norms (beliefs about both what is successful and what is right in worldwide politics); strategic cultures (‘sets of beliefs about the fundamental character of international politics and about the best ways of coping with it, especially as regards the utility of force and the prospects for cooperation’) (Friedberg, 2005:34); and identities (Wendt, 1999, 1995, 1994). One of the well-defined understandings of identity was suggested by Brubaker and Cooper (2000), who asserted that identity is a foundation for political and social action. A co-operative phenomenon representing similarity among members of a group, identity is understood as both a key feature of collective or individual ‘selfhood’, and the outcome of political or social action, or the result of competing or various discourses.

This definition of identity continues to be one the most discussed issues in IR theory and political science. Kant (1991) and Hegel (1999) believe that identity cannot be formed exclusively through simultaneous construction and the negative stereotype of the ‘other’. While some scholars such as Huntington (1996) and Schmitt (1976) apply this binary in their works, others, Nietzsche, Connolly (2000), and Habermas (1984; 1990) consider methods of overcoming it. Lebow (2008), drawing on Homer’s Iliad, challenges the debate by suggesting that identities usually emerge prior to the creation of ‘others’, and that ‘others’ do not need to become linked with negative stereotypes. The principal focus of Hegel, Kant and Schmitt is based on the formation of one’s own national identity, they understood identity along with the creation of difference, and also as an ‘encounter with a pre-existing difference’ (Lebow, 2008).

The negative perception of ‘others’, or the ‘us’ and ‘others’ discourse, found its reflection in the ideas of populism (to be more specific, ‘new’ populism). While some academics argue that there is no clear sense of how to identify the core of populism, and give one definition as the nature of this phenomenon (Mouzelis 1985; Taguieff, 1995), others identified populism based on contextual, variegated and universal approaches. Works based on historical case studies, using contextual approaches, describe historical examples of populism, such as agrarian radicalism, narodnichestvo (in the Russian Empire), Peronism, and ideas of Social Credit. Shils (1956) concluded that populism ‘exists wherever there is an ideology of popular resentment against the order imposed on society by a long-established, differentiated ruling class which is believed to have a monopoly of power, property, breeding and culture’ (Shils, 1956: 100-1). Shils believed that populism is about relations between masses and elites. Kornhauser (1959:103), following Shils’ definition, argues that mass society helps to increase populist democracy, which is opposite to liberal democracy. Di Tella (1965, 1997) considers populism as a variation between the perception of the state by the poor and the elites. Canovan (1981) differentiated agrarian populism and political populism, defining the agrarian form as the attempts by elites to mobilize the rural population. Canovan considers political populism as reactionary, and compares Enoch Powell in the UK to George Wallace in the USA. While in the UK, Powell warned against the risks of immigration for British culture, in the US, Wallace objected to racial unification, and stood as a third party candidate in the 1968 presidential election. Both cases democratised ‘a clash between reactionary, authoritarian, racist, or chauvinistic views at the grass roots, and the progressive, liberal, tolerant cosmopolitan characteristic of the elite’ (Canovan, 1981: 229). Previously populism was considered as differentiation between elites and the masses (Shils, 1956), and the poor and elites (Di Tella, 1965), the mobilization of agrarian population against elites (Canovan, 1981) and political populism – the conflict between intolerant (reactionary, racist) masses and tolerant (progressive, liberal) elites.

More recently, in academia, populism has started to be understood as an opposition to liberalism. In the US journal Telos, populism is interpreted as an alternative to the hegemony of liberalism. These ideas emerged with ‘new’ populism. New populism rejects the harmony of the post-war environment, and tries to rebuild politics between ideas of immigration, taxation, and regionalism/nationalism (Taggart, 2000). Ideas of cosmopolitanism and internationalism are ‘anathema to populists …’ (ibid, 2000: 96). For this reason ‘new’ populism was associated with ethical nationalism. Thus, new populism is mainly based on ideas of national identities and similarly considers ‘others’ in a negative light (Kant, 1991; Hegel, 1999). Moreover, populism can be understood within direct democracy. Referendums are often assumed as a mechanism for direct democracy and as institutions are constitutionalist, referendums can give consultation for political elites on the voices of the people. Nonetheless, the referendum on June 23rd 2016 was a unique example of how a referendum can change the future of a country and a whole international institution – the European Union.

European Union

Democracy

Liberal theory has been practically implemented in the European Union. In general, it is said that the EU can trace its roots to the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), and the European Economic Community (EEC), created in 1951 and 1958 by the Inner Six states (France, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg, West Germany and Netherlands) (Guardian, 2016). However, in order to understand the organization, its recent changes, and current affairs in Europe, the background of the establishment of the European Union should be carefully considered. While Schmitt (1962: 3) argues that the European search for union began with the chaos of feudalism, the origins of the concept may be traced back as far as seventeenth-century England, when an Oxford University professor, Richard Zouche, proposed in 1650 that local authorities should be permitted to avoid their sovereigns and send embassies to any peace congress to discuss issues about their province (Zouche, 1911). In 1693 William Penn suggested a European Parliament, not in a democratic sense, but as an institution representing not only princes (Schmtt, 1962). His co-religionist, John Bellers, wanted to divide Europe into a hundred constituencies, each with a representative in a European senate (Fry, 1935).

The French Revolution demonstrated that freedom from dynastic rule had invested humanity with the basis for global peace and order (Schmitt, 1962). A League for Peace and Freedom was founded in 1869, and before the year was out Eduard Loewenthal had established the League for the Union of Europe (Guglia, 1954). In 1929, several French statesmen, including Edouard Herriot and Aristide Briand, presented a plan that suggested a federal organization of European states. The Pan-Europeans were triumphant when at last Briand suggested the idea of the League of Nations. When Hitler came to power, this movement’s biggest cell in Berlin was destroyed. Before and after the First World War, the idea of establishing a European Union was periodically promoted (Stirk and Weigall, 1999), however, ‘nationalism distorted the features of Europe’ (Schmitt, 1962:11). Hitler was not interested in organizing European policy; in private Hitler used ‘European’ and ‘German’ as synonyms (Smith, 1962:12).

After the Second World War, Western Europe had suffered tens of millions of deaths, economies were in disarray, cities were in ashes. The new European leaders, Alcide de Gasperi, Konrad Adenauer, Robert Schuman and Jean Monnet, decided to create a new organization based on the principle of liberalism (Russett, 2013). They believed that the failure of democracy in the face of authoritarianism in Germany, Japan, and Italy had significantly contributed to the start of the Second World War. The main idea was to build stable democratic organizations and to eradicate authoritarian ideologies and old nationalism. In this they were assisted by the defeat and discrediting of the old leaders and by institutional variations put in places by the allied occupation of Western Germany (Russet, 2013). The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) became the forerunner of the European Economic Community and was ‘…a first step in the federation of Europe…’ (Barners and Barnes, 1995:1). The institutional framework of the ESCS formed the foundation of the institutional context of the European Union while ESCS was integrated into the Treaties of Rome in 1957. The European Economic Community and EURATOM were founded as the result of treaties signed in 1958. Signing the Maastricht Treaty in 1993 marked the establishment of the European Union. As most scholars conclude, the success of the EU made other representatives of Europe (mainly Eastern Europe), ‘knock at the door’ and begin to build ‘new’ democracies.

Economic independence

Economic integration means that EU economies together form a much larger European economy. The first reason behind this is to safeguard the economic well-being of EU members, and the second to develop political integration (Barners and Barnes,1995:52-53). The Single Market is an economic environment without domestic borders, where there is a free movement of people, capital, services, and goods. The EU obtains several supranational powers, and accumulates taxes (fees) from all member-states. The European Commission enforces an extensive range of joint guidelines. The Council is an executive institution where essential decisions are made by a weighted-voting scheme, as a result, a small minority of Europe’s population or states cannot block action. The European Parliament is elected by the citizens of the members. In 1999 a European Central Bank took over the dynamic area of monetary policy, while the Euro is the common currency for twenty-five states. Decisions on spending and taxation remained under domestic control, leading most European countries to take on excessive public debt and run payment deficits, which could not be continued. This became a full-blown crisis in 2011, and remains a serious threat to economic growth and political stability. Despite this, no member of the European Union withdrew. Another issue shaped the European Union – the absence of a single ‘European identity’ and the perception of ‘newcomers’, who very quickly started to build socialism from democracy in their states, and became perceived as ‘others’ in a negative way.

International institution:

European Union and its members

The European Union is a politico-economic union consisting of 28 states (officially, the UK is still considered an EU member). The EU states below are presented in the order that each was accepted as a member: Belgium (founder), France (founder), Italy (founder), Luxembourg (founder), the Netherlands (founder), Germany (founder), Ireland (1973), Denmark (1973), the United Kingdom (1973), Greece (1981), Portugal (1986), Spain (1986), Sweden (1995), Austria (1995), Finland (1995), the Republic of Cyprus (2004), Malta (2004), Czech Republic (2004), Slovakia (2004), Slovenia (2004), Estonia (2004), Hungary (2004), Latvia (2004), Lithuania (2004), Poland (2004), Bulgaria (2007), Romania (2007), Croatia (2013). While each became part of the union, they have very different backgrounds. Stirk and Weigal (1999:182) explain that: ‘integration in east Europe can appear as part of military and economic competition with the capitalist west, which the socialist east ultimately lost’. There were significant differences between East and West. There was a greater ideological conformity in the east, strengthened by the idea of socialist or proletarian internationalism. In addition, the USSR got a privileged place for the first socialist states. The USSR was a member of the Warsaw Treaty Organization (WTO) and the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA), along with other communist states (The Polish People’s Republic, The People of Republic of Bulgaria, the People’s Republic of Bulgaria, the People’s Republic of Romania, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, the Hungarian People’s Republic, the German Democratic Republic and the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania). In Western Europe, the corresponding superpower, the US, was a member of NATO. The American side supported integration, and insisted that the Marshal Plan aid for European reclamation from the Second World War would be matched by a new institution – the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (Stirk and Weigall, 1999; Barners and Barnes, 1995). As Wallace (1990) concluded, Eastern Europe was on the other side of the ‘iron curtain’, powerfully integrated into the Soviet ‘bloc’. During the past 40 years prior to the 1990s, ‘Europe’ has mostly been understood as a term for Western Europe (Wallace, 1990). The historical background of political cooperation within the EU demonstrates that there are differences between members of the EU.

The importance of identifying a ‘European identity’ was discussed within the Commission, however, based on liberalist ideas, identities were not seriously considered for peaceful cooperation between states. In the 1970s and 1980s there were cultural initiatives to find a ‘European identity’ within the Commission, to title ‘a People’s Europe’ (Zwaan, 1986), which could aid the process of political and economic unification; others believed that separating culture from economy was a fundamental policy (Witte, 1990). They opposed the idea of building a ‘European identity’, and highlighted that European integration originated in the idea of providing economic unification, peaceful coexistence and political collaboration without affecting EU members’ identities. With the extremely varied cultures and histories of these states in mind, by applying Brubaker and Cooper’s definition of identity, it is arguable that after 2004, a coherent ‘EU identity’ might not have been possible. The newest members became ‘others’; states that had developed very differently, and whose cultures and historical heritage contrasted starkly with that of the states that joined in the 1980s and 1990s. A liberalist interpretation might be that the success of the EU is evident in its role (as an international institution) in ensuring peaceful cohesion and collaboration between states with considerable differences and priorities. However, a constructivist interpretation would point out that while some members clearly benefit from the union, representatives from other states have begun to protest that their countries’ individual identities are being compromised, and have expressed concern for the future development of their countries. This was certainly the case for the United Kingdom.

‘Brexit means Brexit’

The former British Prime Minister David Cameron campaigned for the referendum on EU membership. Previously, the UK resisted some key EU innovations, such as the single currency and the Schengen Treaty on border controls. The main concerns that the British leadership presented on remaining in the EU were the economic strain of the payment of benefits to migrants, and the need for greater protection for EU members in the Eurozone (BBC, 2017). During the lead up to the referendum, many issues were targeted by both the Remain and Leave campaigns. Much of the controversy stemmed from debates over subjects such as economy, sovereignty, NHS/Health, defence/foreign policy, education, welfare, environment, crime/justice, housing, transport, local government, and immigration (Moore and Ramsay, 2017).

In the 18 months leading up to the referendum, immigration had reliably been considered as one of top three problems facing the UK. In 16 of the 18 months it was viewed as the key issue. One of the main arguments of the winning side – the Leave campaign – was immigration. A few days after the official campaign began, Sir Lynton Crosby wrote: ‘currently 41 per cent of the British population would vote for Leave. But 52 per cent of the British population say that leaving the EU would improve the UK’s immigration system. There is a therefore a misalignment’. Crosby suggested that to win over the other 11%, the Leave campaign would have to make immigration a greater issue than it already was (Moore and Ramsay, 2017). Leave leaders worked hard to make it one of the key issues of their campaign. On April 16th, Boris Johnson said: ‘In return [for membership of the EU] we get uncontrolled immigration, which puts unsustainable pressure on our vital public services as well on jobs, housing and school places’ (ITV, 2016). Iain Duncan Smith, while giving a speech in Ipswich about immigration, mentioned that immigration added the number of ‘a city the size of Newcastle or Plymouth’ to the United Kingdom every year. Michael Gove (Daily Mail, 2016) wrote a paper highlighting the number of Albanian prisoners in British jails. Gove wrote that these people were about to be provided free access to UK schools, welfare and homes. Nigel Farage presented an anti-migrant poster, promoting voters to ‘take back control of our borders’, showing a queue of refugees and migrants on the Croatia-Slovenia border – part of Europe’s passport-free Schengen area (The Guardian, 2016). Critics pointed out the image’s unintentional similarity to Nazi propaganda footage of migrants broadcast in a BBC documentary from 2005.

By contrast, former Prime Minister David Cameron, one of the leaders of the Remain campaign, argued that the UK’s membership of the EU made it stronger, increased economic development through immigration, and protected workers’ rights (Open migration, 2016). Tony Blair, Gordon Brown and Jeremy Corbyn presented immigration positively. Corbyn said to ITV that ‘migration actually is a plus to our economy’ (2016), Tony Blair said that eastern Europeans ‘contribute far more in taxes than they ever take in benefits’ (Express, 2016) and they are ‘good members of our community’ and ‘hard-working people’. Taking into consideration the previously discussed views of constructivists, the identity of other EU members became one of the main weapons for both campaigns. However, the Leave campaign used ‘others’ in the negative way as suggested by Schmitt (1976). The national identity, or possible ‘European identity’, was important for keeping peace and cooperation within the European Union.

The new development of the United Kingdom will be influenced by a focus on developing a sense of the state’s identity. On the 5th October 2016 the new Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Theresa May advocated what some have interpreted as a new ‘illiberal’ direction for the state (Economist, 2016:1), describing Brexit as a ‘quiet revolution’, and a ‘turning point’ in the history of the UK: ‘Time to reject the ideological templates provided by the socialist left and the libertarian right and to embrace a new centre ground in which government steps up’. Mrs May announced that order and discipline would be promoted, borders strengthened, foreign workers kept out, and patriotism respected (Economist, 2016:1). ‘If you believe you’re a citizen of the world, you’re a citizen of nowhere. You don’t understand what the word citizenship means’, Mrs May proclaimed, emphasising the role of British identity for the future of the country.

Initially, as Mrs May triggered the process of withdrawal from the European Union by invoking Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty on 29th March 2017, the UK was expected to leave on 29th March 2019. However, in her speech in Florence on 22nd September 2017, May set out her plans for a two-year post-Brexit transition period, and explored the possibility of a new agreement between the UK and the EU. The Prime Minister said: ‘We are proposing a bold new strategic agreement that provides a comprehensive framework for future security, law enforcement and criminal justice co-operation: a treaty between the UK and the EU’ (Financial Times, 2017:1). For now challenges in whether Brexit will be ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ continue. However, as Brexit is demonstrating, the portrayal of ‘others’ in negative way influenced the UK’s decision to withdraw from the EU more than any other factor. In other words, it is arguable that when a negative perception of others became associated with national identity, the core of liberalism – international institutionalism – stopped working.

French elections 2017

The French elections of 2017 became the most important political event after the Brexit vote within the European Union. The reason for this was the essential role that France took within the EU. Moreover, the heart of European populism, the Front National (FN) party with its leader, Marine Le Pen, welcomed Britain’s decision to leave the EU as ‘a victory of freedom’. Le Pen had called for a French referendum over the previous three years, while standing in presidential elections. The futures of France, the European Union and the Brexit deal depended on this election. Other candidates were either supporters of the EU or suggested a French referendum in their campaigns. For example, Francois Fillon suggested reforming the Schengen travel accords to tighten control of the EU’s outside borders, and stronger EU collaboration on security. However, he suggested yearly quotas fixed by parliament to keep immigration to a strict minimum, to limit the possibility of migrants joining family members already in France, and to limit opportunities to get French citizenship. Jean-Luc Melenchon suggested renegotiating the EU treaties, and that if treaty renegotiation fails, he would consider leaving the EU. Benoit Hamon suggested building a Eurozone assembly with powers to regulate decisions created by the heads of state, to fix a budget and harmonise tax. The first round winners became Ms Le Pen (21.53%) and Mr Macron (23.75%) (Guardian, 2017), with Macron elected the President of France in the second round, with 66.1% of the vote to Le Pen’s 33.9%. The main choice in the second round of these elections was similar to the ‘Leave or Remain’ decision made in the UK; in this case it was between the populist Le Pen and Macron’s ‘neither left nor right’ stance.

Marine Le Pen’s Front National (FN) party was founded by her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen in 1972. By 1984 the party had created a reputation for armed right-wing populism and an electorate of voters, which brought 11% of the vote in the elections to the European Parliament. By 1997 the party had made itself an essential part of the French party system and reached 15 per cent of the vote in parliamentary and presidential elections (Taggart, 2000). When Jean-Marie was leader of the party, a stated aim was to deport three million immigrants, but during Marine’s leadership from 2011, the party started to distance itself from such controversial ideas (BBC, 2017). As a result, the party became more popular in France, gaining 18% of the vote in 2010, and about 24% by 2017. Le Pen’s point of view is based on populist ideas. When she pointed out the key issues of her presidential campaign, she promised to crush ‘Islamic fundamentalism’ and take a hard line against immigration. Ms Le Pen said to supporters that ‘the EU will die’ and that she wanted to exit the Schengen agreement, close French borders and leave the euro, returning to the franc. She promised a ‘Frexit’ within six months of taking power (Guardian, 2017a). The key idea of Marine Le Pen’s campaign was the same as the main idea of the Front National since 1972: keeping France for the French. The results of these two rounds demonstrate that Le Pen considers migrants and representatives of ‘Islamic fundamentalism’ as ‘others’ used in a negative way (Schmitt, 1976). La Pen’s preoccupation with national identity reflects the prevailing concerns of French society, namely, an anxiety about the issue of immigration.

During Macron’s campaign a main concern was the need to resist public spending cuts and economic fragility (Downing, 2017), however it is essential to consider his opinion about immigration as well. Showing an opposite approach to Le Pen, he claimed he would be a president of ‘patriots’ against the ‘nationalist threat’ (Guardian, 2017). Mr Macron didn’t view France as shut off from foreigners in the future. He also suggested, as a solution to overcome the migrant issue in French society, the implementation of integration programmes, which would teach migrants French culture and language. Regarding the European Union, Macron suggested that ‘we are in the world’ which is not a ‘closed country’. He is a supporter of the European bloc and has suggested building a European Security Council. In his manifesto he presented the EU as the best ‘guarantee of peace’ and wished to strengthen the EU’s defence measures along with NATO (Express, 2017). Despite the fact that Macron clearly expressed a wish to promote the ideas of liberalism for peaceful cooperation, it seems that immigration and the issue of national identity raise concerns within society, and European leaders cannot ignore this. The issue of national identity is very closely related to the security problems of the state, especially in France. Since 2015, there have been twenty-three terror attacks in France. The future of France and the European Union depends on Macron’s success or failure. Marine Le Pen is still in politics, having an opportunity to be elected in the next presidential elections.

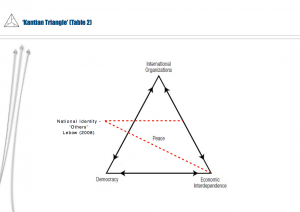

The current development of liberal institutions demonstrates that culture and identity play a more significant role for the states than establishing a liberal world order. The Kantian Triangle, which consists of democracy, economic interconnection, and international institutions, does not reflect the reality of current EU developments. A liberal democracy that ignores national identity could become a populist democracy, as in the case of Brexit. The French case also demonstrates that supporters of populism are increasing in number, and that it is essential to deal with the issue of national identity. It seems that rather than rejecting discussion of national identity, or viewing it as a negative concept, national identity should be considered seriously and positively by European politicians (Table 2). If the European Union aims to develop successfully in the future, it needs to reframe ‘national identity’ in a positive light (not as the extreme far right/the populists do), and to understand that national identities are essential for every state. Having a range of identities within the European Union must be understood as a sign of diversity and strength rather than a negative concept, as it was presented in the example of the Brexit vote or by Le Pen and Fillon in their French presidential election campaigns.

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)

International organization: origins and member’s identities

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) was founded in 1981 by Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman and the United Arab Emirates, all of which faced similar challenges and threats under the regional political circumstances and similar historical background. Being under the former British umbrella of armed and political suzerainty, the Gulf monarchies were keeping more independent from each other. Saudi Arabia was a fully independent state mainly focusing on domestic policies. Britain remained in actual control of all greater regional issues, so there was a necessity for the individual countries to take advantages of suggested cooperation. However, in the early 1960s the political events were changed in the Gulf: the accession of Kuwait to full independence in 1961 serving a message that Britain will finally abandon its total authority in that area. The British began to encourage the smaller sheikhdoms of the so-called Trucial States to think about larger cooperation between them. In the 1960s, the British revealed to the Gulf rulers their plan to totally withdraw from the Gulf. In 1971 the Dubai Agreement was signed, under that Qatar, Bahrain and seven Trucial Sheikhdoms of Abu Dhabi, Sharjah, Dubai, Ajman, Fujairah, Ras al Khaimah and Umm al Quwain that meant joining together in some kind of a federation or union. The next year, when Britain announced its withdrawal from its colonies and bases to the east of Suez, containing the Arabian Gulf, the nine sheiks and emirs signed the agreement to form the United Arab Emirates (UAE). However, only three years after the UAE came into being, Bahrain and Qatar decided to live as independent counties. Nonetheless, in the 1970s, all countries – with the former British-protected countries fully independent and with Oman having ended its era of isolation with succession of power of Sultan Qaboos – were interested in cooperation and the establishment of unity.

The unification of the Gulf was not achieved in one day; there was a long wait of five years for this establishment. In 1976, the foreign ministers of Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Iran, and Iraq had a meeting in Muscat to consider Oman’s idea of coordinated regional security and defence policy creation. However, countries could not find consensus of all issues. In 1976, Sheikh Jaber al Ahmad al Sabah, the 3rd Emir of Kuwait, and at that period of time, a crown prince and prime minister, toured the Gulf states to consider joint action to ‘preserve the region’s security and stability in the face of political, economic and security challenges threatening this strategic area’. Thus, Sheikh Jaber officially suggested the creation of a Gulf union as a mechanism for this joint action, with the aims ‘of realizing cooperation in all economic, political, educational and informational fields’ (Christie, 1987: 8-9). Over the five following years, there were a number of meetings and discussions to form the GCC. Kuwait’s exploratory discourses with the UAE led to the creation of a joint ministerial council of the respective prime ministers of the two states. Moreover, the consultations with Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain and Oman, were equally successful and everybody formally authorized the concept of a Gulf union. However, the overthrow of the Shah of Iran in 1979 and the creation of the revolutionary regime of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini completely changed the security of the Gulf. Some believe that Iran might fill the power vacuum and indeed this contributed to speeding up the process of the establishment of a Gulf union. Moreover, in December 1979 the USSR’s intervention in Afghanistan worsened relations between Iran and Iraq, and contributed to vulnerabilities of six monarchies and emergence of a Gulf union. In early February 1981, foreign ministers of six countries met in Riyadh and unanimously agreed on the creation of a Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). After three months, the Charter was signed in Abu Dhabi and the GCC came into formal existence. Thus, the creation of the GCC was not only related to threat perception (Iranian revolution, Iran-Iraq war, Soviet invasion to Afghanistan), it took many discussions and time for the idea of cooperation for cultural, economic, social, political issues, to emerge.

In contrast to the establishment of the EU, the six founding members of the GCC share many similarities, constituting a unique ‘Gulf’ identity. While all other alliances of separate states must absorb different cultures, languages, and political systems, the GCC states share a common religion, Islam; a common language, Arabic; similar social structures; closely comparable standards of economic growth; close systems of government; a shared geography, and collective culture (Christie, 1987). For example, nationality affects access, residence, even who can marry whom (Dresch, 2005). There are four circles of identity in the Gulf: fellow citizen (muwatin), Gulf (khaliji), Arab, and foreign (ajnabi) (Kapiszewski 2001:179-80). Scholars argue that the threat to culture could be found in the numbers of immigrants in the Gulf (Khalaf 1992). Gulf unity remains essential for cooperation between states (Gause 1994: 87-8), as non-nationals have no role in any liberalization policies in the GCC. ‘They [non-nationals] cannot vote, and their voices are nearly invisible in the liberalized political space created in the past few years’ (Teitelbaum, 2009: 18).

Economic integration

The GDP of the GCC in 2013 was $1.62 trillion comprising – $921 billion in gross exports and $514 billion in gross imports. The GCC economy was rated the fifth strongest in the world, which indicates the power of the GCC in the global economic arena and its potential attraction to investors. The GCC’s economic integration project started in 1981, when the GCC leaders signed an agreement on economic unity in Riyadh. Among the many ideas covered were the cross-border movement of citizens, adaptable capital flows, and collaboration around issues of trade, technology, transport, development, and fiscal and financial cooperation. In December 2001, the GCC rulers ratified an updated version of the agreement. The updated agreement included information about facilitating the creation of the GCC customs union, in keeping with nationwide and worldwide economic trends, a joint GCC market, and the yet-to-be-instituted common currency. By the end of 2008, the GCC states had created a custom union with streamlined measures, customs standards and legislation. The same year, the members decided to establish a joint market. This required the removal of restrictions on the movement of individuals and capital. This also meant that all GCC citizens would be permitted to own property and do business in any of the six states, and would be treated as natural-born citizens. By 2005, the GCC agreed to create a fiscal council that would later become a GCC central bank. In 2001, the states agreed to peg their currencies to the US dollar, however, after discussion in 2005, 2007, and 2010, the launch of a shared currency was postponed (Abdulqaber, 2015).

With all these achievements, the process of economic integration is slow, due to the poor private sector contribution to the GDP, the lack of a sophisticated transport network, political disputes, and some states’ incapability to meet economic integration standards. For example, Hanieh (2011: 145) suggests the idea of Khaleeji (literally translated as ‘Gulf’) Capital, which means a common pan-Gulf Arab identity that sets citizens of the region apart from the other parts of the Middle East. Khaleeji Capital does not mean the loss of ‘national identity’, but in contrast a perspective towards growth at the pan-GCC scale. The key of Khaleeji Capital is structured around a Saudi-Emirati axis, along with other GCC conglomerates becoming ‘subordinate partners within interlocking hierarchical structures’ (Hanieth, 2011:2). In other words, the economic integration (creation of custom union, joint GCC market) becomes an important but not crucial factor in the strength of the GCC cooperation (as liberalism suggests). The main vital element of cooperation could be understood as national identity.

Non-democracy

The Kantian triangle suggests that one of the vital elements for peaceful cooperation among members is democracy. Christie (1987:13) believes that ‘Common language, religion and culture may be the bricks of the GCC edifice; the coincidence of matching government rule is the cement that binds them together’. Thus, the strength of the GCC is in their political systems. Within academic literature there is a debate over the conceptualization of their governance. The six members of the GCC are among the world’s last true monarchies (Peterson, 2009). While one academic suggests that Gulf societies are viewed as the most conservative ones worldwide, and the rulers of the Gulf are referred to by Western media as ‘autocratic’, others believe the political systems are neither autocracy nor democracy, instead characterizing Kuwait’s regime as an ethnocracy (Longva, 2009). Moreover, Kedourie (2009:1) suggests that Arab political tradition holds nothing ‘which might make familiar, or indeed intelligible, the organization ideas of constitutional and representative government’ adding that ‘those who say that democracy is the only remedy for the Arab world disregard a long experience which clearly shows that democracy has been tried in many countries and uniformly failed’. Teitelbaum (2009: 5) in Political Liberalization of the Persian Gulf (2009) clarifies that the book concentrates on political liberalization and not democratization, ‘since democracy, probably most succinctly defined as the freely and regularly practiced replacing of leaders by universal suffrage, does not exist in the Gulf, nor is it expected to in the foreseeable future’. Due to the fact that in the literature there is no clear understanding of the Gulf regime, I will describe it as a ‘non-democracy’.

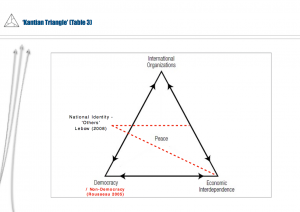

While the European Union depended on democracy as a key element of strong, peaceful cooperation, the GCC’s successful development since 1981 demonstrates the opposite – being the world’s last monarchies (non-democracies) makes them even stronger because they depend on each other. The GCC’s cooperation has not been perfect over the last thirty-six years since, as will be discussed, there have been some crises between them, however, the non-democratic GCC states have had no conflicts between each other. It is arguable then that they have been living peacefully, and have solved their misunderstandings by diplomatic means (Table 3).

Oman: Remain or Leave?

The outcome of the Brexit vote raised a lot of concerns, not solely within the European Union, but within GCC member societies. One of the earliest responses to Brexit came from an official statement by Oman, a representative of the Gulf Cooperation Council, which described Brexit as ‘a courageous historical decision’ (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Oman, 2016). Despite the UAE and Bahrain’s comments about these issues, Oman’s comment led to a discussion about the withdrawal of the country from the GCC. Indeed, Oman is known for its unique and independent foreign policy (Baabood, 2005). Concerns were previously raised about the future of Oman within the organization in 2013, when Oman refused to join the GCC Union. In 2011, Oman also did not agree with the Saudi proposal for the development of a unified GCC (Al –Rashhed, 2013). One of the explanations for why Oman implements such unique foreign policy is also related to Oman’s society, political culture and economy (Baabood, 2017). Since the early 1970s, when Sultan Qaboos came to power, Oman’s foreign policy started to emerge in this manner towards other Gulf states. Omani society has mostly been influenced by Ibadism, a sect of Islam that is neither Shia nor Sunni. The population is heterogeneous, containing an ethnic and religious combination attributable mainly to the history of tribal migrations, maritime trade and relations with the rest of the world: Arabs, Baluchis, Zanzibaris, Indians (Hindus, Liwatiyath), Bayasira, Zatutis, Baharna, Ajam, Sonora, Shihuh (Peterson, 1978; Riphenburg, 1998). Qaboos was able to replace the competition between tribalism and clannism (asabiyaat) by establishing himself as a single ruler. Thus, ‘all the old trends of identifying the Omani people were abolished and replaced by the reinvention of the Omani identity, leading to a process of national unification that evolved around the person of the Sultan’ (Babood, 2017:112). Two main foundations built Sultan Qaboos’ policy: the Sultan’s capability to resolve matters linked to the country boundaries, and Omani identity. Moreover, Qaboos was able to use oil income to consolidate his power through a redistribution system, as all GCC states do. The idea of national identity (because the ethnic, cultural and historical development of the country helped to establish ‘Omani identity’) that affected the implementation of the independent foreign policy in the Omani case, and increased populist ideas in the European case, put the future of the international organizations into question. However, while in the Brexit case, national identity and its reflection of the issue of immigration suggest the negative interpretation of ‘others’ (Hegel, 1999; Kant, 1991; and Schmitt, 1976), in the GCC case, even independent foreign policy and the creation of different identities (‘Omani identity’) is understood through Lebow’s (2008) explanation of ‘others’ in a positive sense.

Observers believe that integration between the GCC states will continue in the future. Alothaimin points to Oman’s strong integration within the GCC to suggest that it is very difficult to imagine Oman’s withdrawal after more than 35 years. Oman is involved with about 46 ministerial committees, 350 working committees and 700 meetings annually (two meetings a day) with the participation of 13 thousands GCC officials from various sectors. With so much intertwining between Oman and the rest of the GCC, Alothaimin is confident that this relationship will ‘remain solid’ (Interview, 2017). Alsulami also emphasised the strong cooperation within the GCC states, stating that Oman is one of the main founders of the GCC, and it was also the state which proposed the establishment of a united army (Peninsula Shield Force) for the GCC. Moreover, Oman has received financial aid from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, UAE and Kuwait. Nonetheless, Alsulami mentioned that for historical and sometimes cultural reasons, Oman also looks at itself differently from the other member countries of the GCC. Pointing out security, financial and historical reasons, Alsulami suggests that it would be very difficult for Oman to withdraw from the GCC (Interview, 2017). Alsulami described the future of the GCC as ‘stronger than many people think’. Similarly, Alothaimin suggests that due to ‘the challenges that surround the region and the world, a stronger union among the six states has become a necessity rather than a choice and member states realize this and work for it’.

The motivation behind Oman’s official statement was related to the strong and historical relationship between Oman and the UK. Alsulami said that it should be viewed as ‘a supportive step to the UK rather than applying to Omani domestic issues’. Alothaimin also suggests that Oman’s statement was designed to ‘appear supportive of the “will of the people” in the UK’, referring to their role as a ‘close ally of London’. Indeed, before the First World War, Britain, Russia, France and Germany competed to dominate Oman and the south-eastern shore of the Gulf. When oil was discovered in southern Iran in 1908, it became the key for Britain’s policies in the Gulf (El-Solh, 2000). Along with European imperial competitions, Oman was the key to the security of the maritime approaches to Britain‘s territories in India. Britain was able to influence the region using force, threats or diplomatic initiatives (El-Solh, 2000). For example, in 1869 when the British leadership felt the Ottoman Government was encouraging rebellion in Dhofar against the Sultan of Masqat, the British rulers warned that no ‘foreign interference in Dhofar would be tolerated’ (FO 54/27, Simla to Bushire, 1896). For providing protection, Britain concluded a number of agreements with the Sultan of Masqat and with tribal leaders, the British authorities concluded an agreement with the Sultan of Masqat and Oman became independent in 1793 five years after the Sultanate (Cain and Hopkins 1993:418). Thus, treaties entitled Britain to have ‘a preponderating influence’ in Masqat, without affecting, in principle, the independence of the Sultanate and its foreign policy (FO 54/36, 1905: 96-8). Omani and UK historical ties are so long and strong, that Oman’s message mainly was related to the support of the Britain’s decision, rather than demonstration of the possibilities of its own withdrawal from the GCC.

How national identities will help to recover deteriorating relations between the GCC?

Qatar as a case study

When Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani came to power in Qatar in 1995, he created a new foreign policy by building political ties with the US and regional powers such as Iran, and built relations with Israel. Qatar even attempted to influence the region for a short period, which became possible by building alliances with Islamist groups (Muslim Brotherhood, Hamas, Hezbollah, Libyan Fighting Group, Houthis) and by establishing its media (Al Jazeera, Arab 21, Middle East Eye). Qatar’s key means was its wealth. Qatar’s relations with Islamists became the core of crises between its ‘brother’ GCC states, especially Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain, in 2013/2014, and currently in 2017. On the 5th of March 2014, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain withdrew their ambassadors from Doha. This marked the start of a period of unprecedented political tension between the GCC states. At that time, Qatar disagreed with the classification of the MB as a terrorist organization, but rather continued to give them, ‘quiet and generous support’ (The Economist, 2014:1). The rift was resolved with Qatari concessions. Observers believe that the similar national identities helped to overcome the crisis in GCC relations. Alsulami (Interview, 2017) suggests that the similar identities of the GCC states helped Qatar to recover its deteriorating diplomatic relations with the rest of the organisation; and this factor will help to quickly overcome any dispute or disagreement among the GCC.

The second current crisis started in May 2017 when, several days after the US-Arab-Islamic Summit, the official Qatar News Agency ran a report quoting positive comments by the current Emir – Sheikh Tamim about Iran and Hamas (Al Arabiya, 2017). Qatar stated that the Qatar News Agency was hacked. On 5th June, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Yemen, Egypt, the Maldives, and Bahrain cut ties with Qatar, stating that its foreign policies had been undermining stability and security in the region by supporting various terrorist and sectarian groups (such as the Muslim Brotherhood, ISIS, al-Qaeda). On 22nd June, thirteen demands were issued by four Arab countries – the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Egypt – to end the crisis (consisting of cutting relations with Muslim Brotherhood, and other Islamists; shutting down the Al Jazeera news network; downgrading relations with Iran; and closing a Turkish military base). These demands were rejected by Qatar. On 19th July six broad principles for Qatar were suggested by the Arab quartet, to restart the negotiation process (The National, 2017). However, the crisis is still continuing and this dispute has brought uncertainty in the region and globally.

The current discourses focus on the future of the GCC crisis, and the institution itself, dominated by the question of whether Qatar will withdraw from or stay within the GCC. If Qatar withdraws from the GCC, it would probably continue to develop relations with Turkey and Iran, but in this case, Qatar risks becoming dependent on two regional players which are trying to expand their dominance in the region. It should be acknowledged that relations between Qatar, Iran and Turkey are successful mainly because of Qatar’s financial resources, rather than the GCC’s shared cultural and historical heritage. There are two points to consider here: Iran needs Qatar for power projection – to support Iranian shields – Shia militias in the region (such as Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis in Yemen, and the so-called Bahraini Hezbollah), and Iran’s interest in having closer relations with Qatar is related to disturbing Saudi and UAE dominance in the region, and generating conflict between them and Qatar. Turkey is interested in Qatari investment and in strengthening the Muslim Brotherhood presence in the region together with Qatar. For a Turkish presence and security umbrella, Qatar would ‘pay’ with investments. However, as transformative changes in the LNG market approach (Wright, 2017), along with isolation from the GCC (as land and air routes are closed off), the required investments into Qatar itself, investments in Turkey, and further support for Islamists (Muslim Brotherhood, Iranian militias), could put even Qatar in a difficult financial situation in the future. Without Qatar’s primary strength, its wealth, its union with Iran and Turkey would be undermined. In this case, equal partnership would come to an end and Qatar would be viewed as a dependent, weak and secondary state.

The future of the GCC as a whole depends on Qatar, and some argue that Oman could be the second state to withdraw from the GCC, as it implements an independent foreign policy. However, a shared or similar national identity will be one of the key factors in the normalization of the relations between the GCC states, even at such critical moments of cooperation. In other words, if Qatar stays with the GCC, the crisis between Oman and the rest of the GCC will not occur. Thus, the stronger the national identity between members of international organisations, the stronger their union is.

Conclusion

Detailed analysis of the GCC as an international organization demonstrates the essential importance of similarities between national identities among member-states. The Qatar case study demonstrates that even for very critical relationships between the GCC states, national identity served, and will continue to serve, a key role in normalizing relations, and in unification. Due to the culturally varied development of Oman’s identity, ‘others’ can be characterized in a positive way, as suggested by Lebow (2008). As a result, the GCC case study proves the presented ‘Kantian Triangle’ (Table 2) with the additional element of national identity (Lebow, 2008). Moreover, the development of the GCC contradicts Kant’s suggestion that the future of peace can happen only between democratic states, which are key for liberalization. As Rousseau suggested (2005) a union of non-democratic states could be successful as well. Indeed, the non-democratic GCC states have been living peacefully in cooperation for thirty-six years. This uniqueness put them in a position of dependence as the success of one relied on the success of others. Having analysed the current development of Europe, in particular the aftermath of Brexit and the collaboration of the GCC, I propose that the Kantian triangle be redesigned in a quadrilateral configuration, as follows (Table 4):

Diana Galeeva is a PhD candidate at Durham University in the UK.

Bibliography:

Abdulqader, K.S. 2015. GCC’s Economic Cooperation and Integration: Achievements and Hurdles. 31 March. Available at : <http://studies.aljazeera.net/en/dossiers/2015/03/20153316186783839.html>. [Accessed 01 May, 2017].

Al-Rasheed, M. 2013. Omani rejection of GCC union adds insult to injury for Saudi Arabia. 28 November. Available at : < http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/12/oman-rejects-gcc-union-insults-saudi-arabia.html > [Accessed 01 May, 2017].

Alothaimin, I.,2017., interviewed by Galeeva D.

Alsulami, M. 2017. , interviewed by Galeeva D.

Al Arabiya English. 2017. Qatari Emir: Doha has ‘tensions’ with the Donald Trump administration. 24 May. Available at <: https://english.alarabiya.net/en/News/gulf/2017/05/24/Qatar-says-Iran-an-Islamic-power-its-ties-with-Israel-good-.html >[Accessed 24 May 2017].

Barnes, I. and Barnes, P.M. 1995. The Enlarged European Union. Longman Group UK Limited: Essex.

Barakat, S., 2012. The Qatari Spring: Qatar’s Emerging Role in Peacemaking. London: Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States.

Babood, A. 2005. Dynamics and determinations of the GCC state’s foreign policy, with special reference to the EU, in Nonneman, G. (ed.). Analyzing Middle East foreign policies and the relationship with Europe. Lndon and New York: Routledge.

Baabood, A. 2017. Oman’s independent foreign policy, in Almezaini, K. and Rickli, J-M (eds.). The Small Gulf States Foreign and Security Policies before and after the Arab Spring. New York: Routledge.

Blanchard, C., 2008. Qatar: Background and U.S. Relations. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Brubaker, R. and Cooper, F. 2000. Beyond ‘Identity’. Theory and Society, 29 (1), pp. 1-47.

BBC News, 2017. Brexit: All you need to know about the UK leaving the EU. 25 April. Available at: < http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-32810887> [Accessed 01 May, 2017].

Barnhard, G., 2015. The Patient Preacher: Yusuf al-Qaradawi’s Long Game. Hudson Institute, [online] 31 March. Available at: < http://www.hudson.org/research/11177-the-patient-preacher-yusuf-al-qaradawi-s-long-game > [Accessed 1 May 2017].

BBC News. 2017. France elections: What makes Marine Le Pen far right? 10 February. Available at: < http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-38321401> [Accessed 01 May, 2017].

Cain, P.J. and Hopkins, A.G. 1993. British imperialism: innovation and expansion 1688-1914. London: Longman.

Canovan, M. 1981. Populism. London: Junction.

Connolly, W. 1991. Identity/ Difference: Democratic Negotiations of Political Paradox. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Christie, J. 1987. History and Development of the Gulf Cooperation Council: A Brief Overview. In The Gulf Cooperation Council Moderation and Stability in an Interdependent World. ed. by Sandwick, J.A. Colorado: Westview Press.

Dickinson, E., 2014. The Case Against Qatar. Foreign policy, [online] 30 September. Available at: < http://foreignpolicy.com/2014/09/30/the-case-against-qatar/ > [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Dresch,P. 2005. Debates on marriage and nationality in the United Arab Emirates. In Monarchies and Nations Globalization and Identity in the Arab States of the Gulf.ed. Dresch, P. and Piscatori, J. London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd.

Dargin, J., 2007. Qatar’s Natural Gas: The Foreign policy driver. Middle East Policy, 14 (3), pp. 136-42.

Di Tella, T.S. 1997. Populism in the twenty-first century, Government and Opposition, 32, pp.187-200.

Di Tella, T.S. 1965. Populism and reform in Latin America, in C.Veliz (ed.) Obstacles to Change in Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Downing, J. 2017. End of Frexit, bad for Brexit? Macron’s win signals France’s resurgence in Europe. Available at: <http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/brexit/2017/05/08/end-of-frexit-bad-for-brexit-macrons-win-signals-frances-resurgence-in-europe/>[Accessed 01 May, 2017].

De Lage, O., 2005. The Politics of Al Jazeera or the Diplomacy of Doha. In: M. Zayani, ed. 2005. Al Jazeera Phenomenon: Critical Perspective on New Arab Media. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers. pp. 49-65.

El-Agraa, A.M. 1998. The European Union History, Institutions, Economic and Policies. 5th ed. of the Economics of the European Community. Essex.

Express. 2016. They’re hard workers’ Ex-PM Tony Blair DEFENDS opening up Britain to mass immigration. 4 May. Available at:< http://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/666822/Tony-Blair-migrants-Poland-politics-eastern-Europe >[Accessed 01 May, 2017].

Economist. 2016. May’s revolutionary conservatism. 8 October. Available at: < http://www.economist.com/news/britain/21708223-britains-new-prime-minister-signals-new-illiberal-direction-country> [Accessed 01 May, 2017].

Express. 2017. Marine Le Pen vs Emmanuel Macron: Where do they stand on immigration and the EU. Available at: <http://www.express.co.uk/news/world/800900/French-election-2017-Marine-Le-Pen-Emmanuel-macron-immigration-EU-policies>[Accessed 01 May, 2017].

El-Solh, 2000. The Sultanate Oman 1914-1918. (ed). Reading: Ithaca Press.

Fry, A. Ruth.1935.,(ed.) Quaker, Economist and Social Reformer, London.

Guardian, 2017a. Its’ Macron or Le Pen after first round of France’s presidential election. Available at: <

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/23/macron-set-to-face-le-pen-after-first-round-of-french-presidential-election> [Accessed 01 May, 2017].

Guardian. 2017. French presidential election: how the candidates compare. Available at: <

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/04/french-presidential-election-how-the-candidates-compare> [Accessed 01 May, 2017].

Guardian, 2016. Brexit is only way to control immigration, campaigners claim. 25 April. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/apr/25/brexit-is-only-way-to-control-immigration-campaigners-claim >[Accessed 01 May, 2017].

Guardian, 2016. Nigel Farage’s anti-migrant poster reported to police. 16 June. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jun/16/nigel-farage-defends-ukip-breaking-point-poster-queue-of-migrants> [Accessed 01 May, 2017].

Gause, F.G. 1994. Oil Monarchies Domestic and Security Challenges in the Arab Gulf States. New York: Council on Foreign Relations, Inc.

Guglia, O., Kampf um Europa , 1954. Vienna, pp. 36-37.

Habermas, J. 1984-7. A Theory of Communicative Action., 2 vols. and Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hanieh, A. 2011. Capitalism and Class in the Gulf Arab States. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hroub, K., 2012. Qatar and the Arab Spring in Qatar: Aspirations and realities. Political Analysis and Commentary from the Middle East and North Africa, 4, pp. 35-41.

Hegel, G.W.F. 1999. The German Constitution. In Political Writings, ed. Dickey, L. and Nisbet, H., trans. Nisbet, H. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Huntington, S. The Clash of Civilization and the Remarking of the World Order. New York: Simon and Schuster.

ITV, 2016. Boris Johnson in Newcastle on ‘Vote Leave’ campaign.16 April. Available at:

http://www.itv.com/news/tyne-tees/2016-04-16/boris-johnson-in-newcastle-on-vote-leave-campaign/ [Accessed 01 May, 2017].

Kant. I. 1795. Project for a perpetual peace: A philosophical essay by Emanuel Kant profess. London.

Kant, I. 1991. Idea for a Universal History with a Cosmopolitan Purpose. In Kant: Political Writings, ed. Reiss, H. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kamrava, M., 2013. Qatar Small State, Big Politics. New York: University Press.

Kapiszewski, A. 2001. Nations and Expatriates: population and labour dilemmas of the Gulf Cooperation Council states, Reading: Ithaca Press.

Kornhauser, W. 1959. The Politics of Mass Society. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Khatib, L., 2013. Qatar’s foreign policy: the limits of pragmatism. International Affairs, 89 (2), pp. 417- 31.

Khalaf, S. 1992. Gulf societies and the image of unlimited good. Dialectical Anthropology. 17 (1), pp. 53-84.

Lebow, R.N. 2008. Identity and International Relations. SAGE Publication, 22 (4), pp. 473-492.

Longva, A. N. 2005. Expatriates and the Socio-Political System in Kuwait. In Monarchies and Nations Globalization and Identity in the Arab States of the Gulf.ed. Dresch, P. and Piscatori, J. London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd.

Moore, M. and Ramsay, G. 2017. UK media coverage of the 2016 EU Referendum campaign. Available at: < https://www.kcl.ac.uk/sspp/policy-institute/CMCP/UK-media-coverage-of-the-2016-EU-Referendum-campaign.pdf> [Accessed 10 May, 2017)

Mouzelis, N. 1985. On the concept of populism: populist and clientelist modes of incorporation in semi-peripheral politics. Politics and Society, 14, pp. 329-48.

Open Migration. 2016. Brexit and beyond: What will the UK out of Europe mean for migration? Available at: <http://openmigration.org/en/analyses/brexit-and-beyond-what-will-the-uk-out-of-europe-mean-for-migration/>[Accessed 01 May, 2017].

Peterson, J. E. 2016. The Emergence of the Gulf States Studies in Modern History. London: Altajir Trust.

Peterson, J.E. 1978. Oman in the Twentieth Century: Political Foundations of an Emerging State. London: Croom Helm, New York: Barnes and Noble.

Rabi, U., 2009. Qatar’s Relations with Israel: Challenging Arab and Gulf Norms. Middle East Journal, 63 (3), pp. 443-459.

Riphenburg, C.J. 1998. Oman: political development in a changing world. Westport, Conn: Praeger.

Russett, B., 2013.Liberalism. In Dunne, T., Kurki, M. and Smith, S. 5th ed. 2013. International Relations Theories Discipline and Diversity, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rousseau,D., 2005. Democracy and War: Institutions, Norms and the Evolution of International Conflict. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Russett, B. 1993. Grasping the Democratic Peace: Principles for a Post-Cold War World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Schmitt, C. 1976. The Concept of the Political. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Shiraev, E., 2014. International Relations. Oxford: Oxford University Presses.

Scmitt H.A., 1962. The Path to European Union. From the Marshall Plan to the Common Market, Louisiana State University Press, Baron Rouge.

Smith, H.W. 1962. The Oxford handbook of modern German history. Oxford: oxford University Press.

Stirk, M.R. and Weigall, D. 1999. The origins and development of European integration: a reader and commentary. (ed.) London: Pinter.

Shils, E. 1956. The Torment of Secracy: The Background and Consequences of American Security Policies. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Sunday Express, 2016. EU expansion: Which countries are waiting to JOIN?, [online]. 22 June. Available at: < http://www.express.co.uk/news/world/664966/EU-Which-Countries-Waiting-to-Join-European-Union-Turkey-Balkan-States> [Accessed 09 May, 2017].

Taguieff, P-A. 1995. Political science confronts populism. Telos, 103, pp. 9-43.

Taggart, P. 2000. Populism. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Teitelbaum, J. 2009. Political liberalization in the Persian Gulf. London: HURST Publisher Ltd.

The Economist., 2014. The Muslim Brotherhood Islamism is not Longer the Answer. The Economist, [online] 20 December. Available at: < http:// www.economist. com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21636776-political-islam-under-pressure-generals-monarchs-jihadistsand> [Accessed 10 May 2016]

Ulrichsen, C. K., 2014. Qatar and the Arab Spring. London: Hurst & Company.

Wright, S., 2009. Qatar’s Foreign Policy: Geopolitics and Strategic Pillars. In: R. Czulda and K. Gorak-Sosnowska, eds. 2009. The State of Qatar: Economy – Politics – Culture. Lodz: Ibidem Publishing House.

Wallace, W. 1990. The Dynamics of European Integration, RIIA, p.19.

Wendt, A. 1999. Social Theory of International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zouche, R. 1911. An Exposition of Fecial Law and Procedure, or of Law Between Nations, and Questions Concerning the Same, tr. J.L. Brierly, Washington, DC.

Zwaan. D. 1986. The Single European Act: Conclusion of a Unique Document, 23 Common Market Law Review, 747.